Warning: This story includes discussion of suicidal ideation and suicides.

He had endured many tough days with a fog descending on his brain -- fumbling for words, forgetting the reason he left his house, hellish nightmares.

But this was different.

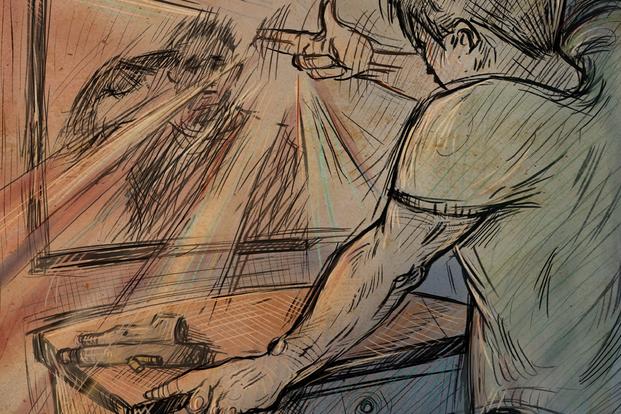

Army Spc. Daniel Williams had barricaded himself inside a bathroom of his home with a loaded .45. Less than a year after seeing combat in Iraq. Williams, who had been trained by the service to detect and destroy weapons of mass destruction, sat in the cramped space, his broad shoulders slumped forward in defeat.

Read part two of this series: Lost Years and Missed Opportunities: How the Pentagon Squandered the Chance to Combat Brain Injuries

Fury had given way to despair. The anger over the loss of a friend to a roadside bomb, frustration at the growing blanks in his memory, and rage at an Army that couldn't get him a psych appointment for six months all collapsed into a burning desire to just make the pain stop.

As Williams' wife pounded on the door, visions of his future faded from view. The physical pain from his injuries -- a torn shoulder, busted back and relentless migraines -- was omnipresent, but the mental fallout from the blast was what moved Williams to put the pistol in his mouth and pull the trigger.

Click.

No bang, just his wife's continued begging and the door splintering open as police officers busted through and grabbed the gun.

They thrust the burly, 6-foot-3-inch soldier into the tub and handcuffed him. After the chaos subsided, one of the officers took the weapon from the house. When he attempted to clear the gun of ammunition, it went off.

"The same round that refused to kill me went off perfectly for him," Williams testified before Congress nearly a decade later.

It would be three more years before Williams, initially diagnosed with an adjustment disorder that later was determined to be post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, began to understand the extent of his injuries from the improvised explosive device that slammed him into the hood of a Humvee and killed his friend while deployed in Iraq.

After a physician finally recommended he get a scan of his brain, Williams realized that what he had experienced was more than PTSD; it was a physical injury from that roadside blast.

In the images, clear as day, were white spots of decay across his otherwise intact cerebrum. The diagnosis -- a traumatic brain injury, or TBI, came in 2007, just as doctors and researchers were beginning to understand the prevalence of these wounds among troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But more than a decade later, researchers also began to put the puzzle pieces together connecting traumatic brain injury and suicide -- something Williams said now makes a lot of sense to him, given his impulsivity.

"I had no regulation of emotions anymore. I only had one response: anger. That was it, anger," Williams said.

A recent study found that the rate of suicide among veterans who had experienced a mild traumatic brain injury, also known as concussion, was three times higher than the general population across the study period, from 2002 to 2018. And those with moderate to severe brain injuries were five times more likely to die by suicide.

The data sets are startling. But with this knowledge, those who work to help affected veterans and conduct research may be able to bend the curve of the suicide trajectory among veterans in the U.S., implementing protocols to prevent injury, improve medical treatment and provide better support to the injured.

TBI, along with post-traumatic stress disorder, became the signature wounds among veterans of the post-9/11 era. While other wars had their associated illnesses -- the scarred lungs from mustard gas in World War I, cancers from exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam, and unexplained symptoms from the 1990-1991 Persian Gulf War -- the diagnosis of TBI and post-traumatic stress disorder recalled the tremors, dizziness, tinnitus and "thousand-yard stare" once described as "shell shock" during WWI and "combat stress reaction" in World War II.

The number of traumatic brain injuries in the post-9/11 wars was higher than anticipated for several reasons, including enemy tactics that relied heavily on explosives triggered remotely to disrupt and destroy, and improvements in battlefield medicine that saved troops who otherwise would have died of their injuries.

As the number of head injuries grew, another epidemic also was on the rise among post-9/11 veterans: suicide. From 2005 to 2017, the suicide rate for veterans ages 18 to 34 jumped by 76%, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Suicide is a complex issue caused by many factors, and experts warn against trying to "solve" the question of why someone takes their own life. Still, after more than two decades of research and at least $165 million spent to study the problem, officials continue to treat it as somewhat of a mystery.

Pentagon and VA officials note that suicides also have risen in the general population in the past two decades. In rolling out an ambitious plan to address suicide in June 2020, officials in the Trump administration told reporters, "There is so much we don't know" about veteran suicide.

And maybe they don't. But a growing body of evidence suggests traumatic brain injury may play a role.

Nearly 460,000 traumatic brain injuries have been diagnosed in service members in the past two decades, 80% of which the Defense Department has classified as "mild" TBI, also known as concussion. The DoD maintains that most troops with a mild TBI are able to return to duty within 10 to 14 days after rest and a gradual resumption of activity. Service members with moderate to severe TBI may have lasting damage, according to the DoD, such as extended headaches, loss of vision, seizures, clumsy movements, confusion, agitation and personality changes.

But as these veterans age and the science evolves regarding concussion, it appears that troops with the mild form of traumatic brain injury, especially those who have had multiple blows to the head, are at higher risk for illnesses like dementia and Alzheimer's disease, and also of death by homicide, accidents and suicide.

The Link

Traumatic brain injury has been the center of heated debate in the military community for nearly two decades. In 2003 and 2004, as troops began returning from combat with injuries from roadside bombs in Afghanistan and Iraq, many had physical injuries but also mental deficits that largely went undetected, undiagnosed and untreated.

At the same time, the number of suicides among active-duty, reserve and Guard members, as well as veterans, began to rise -- puzzling deaths given that, in previous wars, the number of suicides among service members was lower than the general population.

A potential link between the two has begun to be made only in the last several years, most recently by a group of researchers at the University of Texas at San Antonio, who published a study in February that brought the issue to the forefront.

Epidemiologist Jeffrey Howard, a bespectacled professor who sports an insurgency of gray in his beard and has spent a career studying military and veteran public health issues, sought to figure out exactly how many post-9/11 veterans died prematurely from all manner of causes outside combat -- what are known among statisticians as "excess deaths."

According to Howard, the results were surprising, especially deaths involving service members and veterans with TBI. Not only were there significantly higher rates of suicide among those with mild traumatic brain injury as well as moderate to severe brain injuries, veterans with TBI also were more likely to die by accidents or homicides than their counterparts who had never suffered an injury.

Howard's research was one of the first comprehensive studies of the veteran population that made clear how the scourge of TBI continues to visit itself on vets.

"We've known about some of it, like suicide, has been an issue for this population for a while," Howard said during an interview with Military.com. "Until we did this study, it wasn't clear to me that there was an increased risk across all these different causes of death."

Howard, soft-spoken and not prone to hyperbole, described the conclusions of the study in terms of a reckoning of the cost of war.

"It really reflects a need for society-wide rethinking of when we send our military service members to fight," he said.

Howard's research supports what others have been warning for years. In 2018, Danish researchers examining the deaths of 34,500 civilians found that the suicide rate for those with TBI was nearly twice that of people who weren't diagnosed with one. And an annual analysis conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the general U.S. population found that suicide was the top cause of death among those with a traumatic brain injury in 2019.

Yet there remain many holes in scientists' understanding of how significantly TBI contributes to veterans' suicide.

"Although many have speculated about the reasons for the high military suicide rates in the last 20 years, simple answers have been elusive and the reasons for the high rates remain largely unknown," Mark Reger, chief of psychology at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, and two others wrote in the commentary of the same issue of JAMA Network Open that published Howard's research.

An estimated 30,177 active-duty and former U.S. troops have taken their own lives since 2001, according to an analysis by Thomas Suitt for the Costs of War project by Brown and Boston Universities, more than three times the number of personnel killed in post-9/11 combat operations.

It's not known exactly how many had a history of TBI, but their deaths have left a trail of heartbreak, anguish and unanswered questions for loved ones left behind.

A Shattered Veteran, a Grieving Family

Kristina Langford is among those who can no longer hug their loved ones who served in the post-9/11 wars. Her husband Jonny Langford died by suicide in April following a yearslong struggle with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Langford remembers her husband as a vibrant, loving man who was always smiling and simply joyous, from his days riding mountain bikes as a teen to their courtship as a young Army couple. Her Jonny, with the sparkling eyes and deepest dimples that charmed anyone in his orbit, loved vintage cars and dirt bikes, the beach and his sons.

After his first combat deployment in 2005 -- a tour in which his vehicle was struck by an improvised explosive device, or IED -- he became short-tempered and a little forgetful. "Then he started getting paranoid. Like, hyper-vigilant," Langford said.

She suspected that Jonny's changes were the result of combat exposure and stress back during an era when TBI was still not broadly discussed in the military community, and even medical researchers were just beginning to grapple with the scope of the ballooning problem.

Researchers would find that the memory issues, moodiness, anxiety, depression and sleep disruptions common to conditions like PTSD also are characteristic of traumatic brain injury.

Jonny redeployed four years later and was again hit by an IED. After six months of recovery away from combat, he returned to the theater and was injured by a grenade.

Three Purple Hearts. Three traumatic brain injuries in less than five years. And a completely altered personality.

Following a move to Florida to be close to family, Jonny lost his grip on reality. Strangers were watching him, he thought, through cameras hidden in his house. He believed they were using his wife's car radio to monitor his conversations. One afternoon, imaginary invaders entered his backyard. He took his handgun outside and started shooting.

When the police arrived, they confiscated his handgun under a Florida law known as the Baker Act, which allows law enforcement officials and health professionals to commit a person involuntarily to a mental health facility for up to 72 hours.

While Jonny was gone, Kristina hid his AR-15.

Kristina said Jonny had tried to get better. He received experimental hyperbaric oxygen therapy from the VA when he lived in Colorado and nerve block injections while in Hawaii. In Florida, the injections weren't available, so his physicians at the VA put him on a variety of medications.

But when he sought additional pain relief from medical marijuana, the VA cut off his prescription medications. Just days before his death, the couple learned they had been dismissed from the VA's program for family caregivers.

Facing the loss of a safety net and in physical and mental pain, Jonny, unbeknownst to Kristina, found his rifle. He died that day in his home.

"It sounds stupid now, but he promised me he'd never do it," Kristina said.

The sometimes lengthy period of readjustment to civilian life can be particularly fraught for veterans. The sudden upheaval is tied to feelings of grief and loss, physical and mental health problems, employment and financial uncertainty, and adjustment issues. And, notably, a marked increase in the risk of suicide.

"There's a whole set of factors that are impacting these younger service members as they transition out of military service back into civilian life," added Howard. "What these data are saying is that that's exacerbated by these kinds of exposures such as having TBI."

Understanding How TBI Impacts Veterans

Why service members and veterans with TBI may be more susceptible to death by suicide is currently the subject of intense research, but as researchers begin to understand the condition, clues are emerging.

"Even with mild injuries, you can see neurochemical changes and troublesome deficits," Dr. Warren Lux, a neurologist who served as medical director of the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, said in an interview with Military.com. "The other thing that is happening with brain injuries is the frontal lobe is very involved. ... The injured lose the ability to monitor themselves, and they lose the ability to understand consequences."

Researchers are also finding that having multiple TBIs can have a multiplying effect on suicide risk.

A 2013 study of 161 service members found those with multiple TBIs were more likely to experience suicidal thoughts and behaviors than those with one brain injury. And a 2018 study by VA researchers found Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with multiple TBIs were twice as likely to report suicidal ideations than veterans with one or no head injuries.

Official Defense Department TBI statistics do not specify how many troops suffer from multiple injuries, but one study released earlier this year estimated that up to 2.3% of service members annually suffer a repeat TBI.

Mild TBI was the most common injury in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also can occur in scenarios that don't involve combat or an explosive blast. Vehicle accidents, training injuries, even being in close proximity to the discharge of a big gun or artillery can cause a concussion. The CDC estimated about 80% of troop and veteran brain injuries happened outside of deployments.

Figure out how to reduce traumatic brain injury in active-duty troops, and you may reduce the number of veterans at risk for suicide or accidental death, posits Howard.

"After 20 years of war, it is vital to focus attention on what puts veterans at risk for accelerated aging and increased mortality, as well as how it can be mitigated," he said.

After the suicide attempt that ended with police breaking down his bathroom door, Williams became involved with the National Alliance on Mental Illness, rising to chair of the organization's National Veterans and Military Council.

He and the wife who saved his life later got divorced. He has since remarried and is a doting father to his children. He also has found a new purpose: building a veterans' retreat with others who served, as well as a mother whose Marine son died after a long struggle with a traumatic brain injury.

The retreat aims to help Alabama veterans who are among the 460,000 diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury in the past two decades. The goal is to give them renewed hope and purpose, and help prevent the estimated 30,177 suicides among post-9/11 veterans from rising, according to Williams.

"I don't want anybody else to go through this frustration, these problems that I went through," he said.

Williams continues to seek therapy when he feels like he needs it. He gets Botox injections for his migraines and does brain training exercises to keep his mind in shape. He readily admits he will never be like he was before the injury, "ever." Like anyone, he struggles with this fact. But he hopes to never return to his dark days -- for his family, for other veterans, for himself.

"There have been moments when there's no reason for me to be here, honestly, other than God has plans for me and a purpose," Williams said.

Veterans and service members experiencing a mental health emergency can call the Veteran Crisis Line, 988 and press 1. Help also is available by text, 838255, and via chat at VeteransCrisisLine.net.

Editor's note: This is the first of a three-part series on the epidemic of traumatic brain injuries among those who served. You can find part two here and part three here.

-- Patricia Kime can be reached at Patricia.Kime@Military.com. Follow her on Twitter @patriciakime.

-- Rebecca Kheel can be reached at rebecca.kheel@military.com. Follow her on Twitter @reporterkheel.

Related: First Look at the VA's New Toxic Exposure Screening All Vets Will Take When Seeing a Doctor