A blue-ribbon panel on military compensation and retirement will probably recommend changes to basic, special and retirement pays, researchers say.

The congressionally mandated Military Compensation and Retirement Commission will release its long-awaited report Thursday afternoon after a two-year review.

While the document is likely to call for changing certain forms of troop compensation, it probably won't include more radical reforms to cut personal costs, according to a white paper released Tuesday by the Center for a New American Security, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

"Early reports suggest the commission will produce modest recommendations for reform of military compensation, focusing on changes to the calculation of base pay, special pay and retirement," states the document, which was co-authored by senior fellow Phillip Carter and research associate Katherine Kidder.

"These proposals may have more likelihood of enactment in the near term, based on the difficult political environment that currently surrounds military compensation," they added. "However, these ideas will not adequately reach the core questions that now face the military compensation system as the [all-volunteer force] enters its fifth decade."

The commission's report is likely to set off a massive political fight over the future of military compensation. The Defense Department is already bracing for backlash to the legislative proposals, with a special team of high-level officials standing by to review the recommendations and provide feedback to the White House within weeks.

The panel's sweeping changes will include phasing out the military's 20-year defined-benefit retirement plan -- payable immediately upon retirement -- and allowing Tricare beneficiaries to move into the federal health care system, according to a report by Military Times.

Congress has generally agreed with troop advocacy groups in recent years in rejecting or watering down many of the Pentagon's proposals to reduce military personnel costs by curbing such troop benefits as basic allowances for housing, retirement pay and funding that helps subsidize the prices of groceries and other items at commissaries.

During more than a decade of U.S.-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, lawmakers from both parties approved higher-than-proposed pay raises, expanded education benefits for service members and their families through the Post-9/11 GI Bill, and boosted special pays and bonuses to maintain the military's recruiting and retention goals.

With Republicans taking control of the Senate and maintaining power in the House after electoral victories last fall, many members of Congress will oppose any proposals that could hurt troop morale and translate into less household income for military families. Yet the GOP now includes increasingly vocal Tea Party supporters who want to cut all forms of government spending, including defense.

None of the commission's recommendations, if approved, would affect the retirement pay of existing retirees or that slated for currently serving troops. In general, a service member who leaves after 20 years receives half of his or her base pay upon retirement and every year thereafter.

Sen. John McCain, a Republican from Arizona and the new chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, hinted as much in recent weeks when he said, "Anybody who has already joined the military is eligible for those pay and benefits, but as of a certain date, people joining may be subject to changes in those benefits."

As part of the 2013 Balanced Budget Act, lawmakers agreed to a 1 percent cut to the cost-of-living adjustment for future military retirees. Much bigger changes to the military retirement system could be in store, including 401(k)-like plans and lump-sum payments. After all, currently serving or retired service members aren't prohibited from opting into a possible new retirement system.

To offset a reduction of as much as 10 percent in lifetime retirement benefits, the Pentagon has already proposed offering troops cash payments earlier in their careers, including a 401(k)-style benefit at six years of service, a retention bonus at 12 years of service, and a possible lump-sum "transition" bonus at 20 years of service. The options were among those included in a report acting Deputy Defense Secretary Christine Fox submitted last year to commission.

At least one survey has suggested more troops would support an overhaul to the pension system -- even if they receive less money in the long term -- so long as they get a lump-sum retirement check when they leave.

Pentagon officials have said the changes are needed curb personnel costs, which are budgeted at $177 billion in fiscal 2015, or more than a third of the department's non-war budget of $496 billion. Including civilian personnel, the percentage rises to almost half of the spending plan.

The CNAS researchers noted that the Pentagon currently supports some 2.3 million retirees, a population that will soon exceed the size of the active and reserve forces. "If current cost trends continue, and considering both retirement pay and retirement health benefits, DoD will soon pay more to support its retired military population than its current force," they wrote.

Officials at the Military Officers Association of America, a powerful troop advocacy group in Alexandria, Virginia, have argued that manpower costs consume about the same share of the defense budget as they did in the 1980s. The increased personnel spending helped eliminate a pay gap between the military and civilian sector, and expand troop benefits that improved the quality of the force, they said.

The CNAS researchers took aim at these arguments.

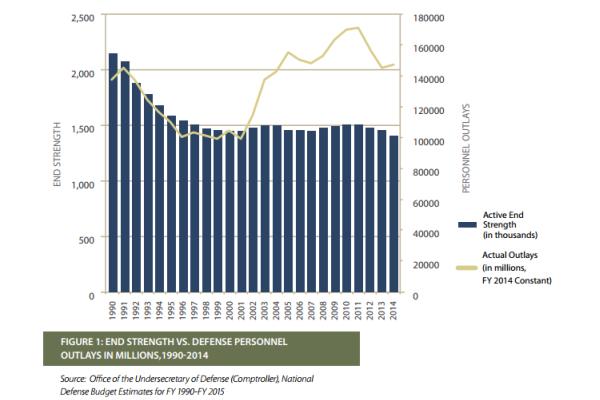

They noted that the overall size of the active-duty force has declined since that time, from more than 2.1 million troops in 1990 to less than 1.4 million troops in 2015. "Defense personnel spending in 2015 is roughly equal to defense personnel spending in 1990, in constant dollars, even though there are roughly 759,000 fewer active and reserve service members than 25 years ago," they wrote.

They also pointed out that the median civilian earnings for the 25- to 34-year-old age group increased just 4 percent, from $29,526 in 1990 to $30,759 in 2013, while military compensation rose an average of 17 percent during the same period. "Interestingly, service members fared significantly better than median U.S. civilian workers aged 25-34 with respect to compensation," they wrote.

-- Brendan McGarry can be reached at Brendan.McGarry@monster.com.