The Army is saving a huge mural left behind by Baron Rudolph Charles Von Ripper before he went off to fight Nazis, earning a battlefield commission, two Silver Stars and two Purple Hearts in the Italian campaign.

Von Ripper, already an acclaimed artist, survivor of a Nazi concentration camp and then a 38-year-old Army recruit in training at Fort Bliss, Texas, painted the 11-by-26 foot mural in 1943 around two windows on the wall of a library building at the base as his gift to the diverse America of his imagination.

Whether he had permission at the time to paint on the wall was unclear, but authorization was never an overriding concern for Von Ripper, who lived the kind of daring life that fascinated Ernie Pyle, the most celebrated of the World War II correspondents.

Read Next: Army and Air Force Run Out of Female Hot Weather Uniforms Amid Summer Heat Wave

"He's the kind they write books about," said Pyle, who came to know Von Ripper in Italy and was in awe of his talents, both as an artist and as a skilled combat veteran of several conflicts.

Von Ripper was genuine Austrian royalty, the son of a general who was aide-de-camp to the last Habsburg Austro-Hungarian king, Charles I, but the ordinary GIs he served with in the "Red Bull" 34th Infantry Division just called him "Rip."

If they had ever made him fill out a resume when he cajoled the Army into letting him enlist, supposedly for "limited duty" in deference to his age and old war wounds, nobody would have believed it.

He ran off to join the French Foreign Legion at age 19 and served two years in Syria, where he was wounded in the chest and knee fighting Druze rebels. After that, it was back to Europe and jobs as a circus clown, coal miner, sawmill worker and anything else he could pick up while continuing his art studies, according to several histories and Pyle's collection of dispatches called "Brave Men."

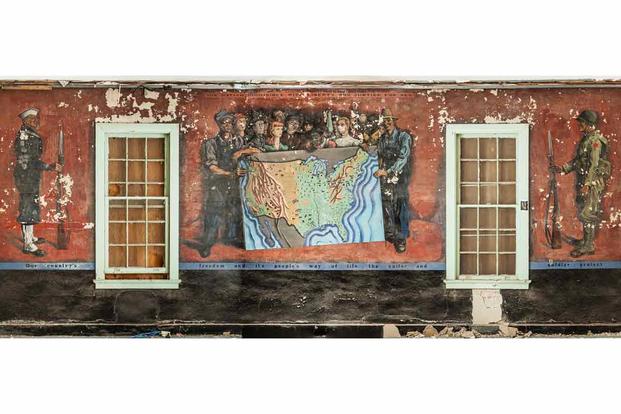

The mural in Texas, left to slowly fade for decades, depicted a soldier and a sailor on either side guarding a diverse cast of Americans holding up a map of the United States in the middle.

The caption written for the mural by Von Ripper, who would become a U.S citizen during the war, read: "Our Country's freedom and its People's Way of life -- The Soldier and Sailor Protect."

In an article published upon the completion of the mural, the El Paso Times noted that the Americans grouped in the center "represent the men who work with muscle and brawn, the thinkers, farmers, artists, musicians, doctors, lawyers, nurses, Negroes, baseball players, college boys and girls, men, women, children -- all who make up a great free nation."

The article also quoted Von Ripper on whether he was homesick for native Austria. "Of course, I think with tenderness of Vienna as it used to be," he said, "but now I never want to return there, even after the war, because I cannot bear to think of the years of horror and the hatred which will follow the war."

The Army stated in 2019 that the mural would be preserved. But the El Paso Historical Society raised concerns that the "decommissioned" Building 7167 housing the mural and the mural itself would be demolished if a proposed lease for the property to the city of El Paso went through.

Laura Cruz-Acosta, strategic communications director for the city of El Paso, confirmed that the city is talking with the Defense Department about the building, but when asked in emails from Military.com last month whether the status of the mural was part of the discussions, she said, "No, we're not at that point."

Numerous inquiries from Military.com with the Army, Fort Bliss, the city of El Paso, the El Paso Historical Society and the Texas Historical Commission failed to get a definitive answer on what would happen to the mural. Then, earlier this month, a one-line statement came from the Fort Bliss public affairs office indicating that the mural would be saved.

"The Army has no plans and does not intend to convey this property," said the statement from Gilbert Telles of Fort Bliss public affairs. Fort Bliss also passed on a detailed plan from the base Directorate of Public Works to preserve the mural.

Hitler's 'Hymn of Hate' -- the Time Magazine Cover

There was always the whiff of danger and possibly a few international felonies about Von Ripper. At one point, he went to China, supposedly to make documentaries, but some gun running on the side was suspected. The story went that the China gig fell through when his boss was shot dead in a Shanghai bar brawl.

Then it was on to Berlin, where he fell in with the anti-fascist art crowd and put out satiric sketches about the Nazis that drew the attention of the Gestapo in 1934. He was beaten, tortured and then sent to a concentration camp. But he was still Austrian royalty, and somehow the Austrians secured his release with the proviso that he never return to Germany or anyplace else controlled by the Germans.

Von Ripper, now holding a grudge, went to Spain to fight in its civil war with the Republicans against Francisco Franco's Nationalists, who were backed by the Germans and Italians. He was serving as an aerial gunner in a bomber supplied to the Republicans by the Soviet Union when his aircraft was shot down in 1937.

He managed to bail out and parachuted into Madrid with a leg riddled with shrapnel. Doctors wanted to amputate, but he refused. Then in 1938, Von Ripper made his way to New York City, where he was taken in by the thriving Greenwich Village arts community.

At the time, a collection of his surrealist works titled "Ecrasez L'infame," or "To Crush Tyranny," had caused a sensation in London in an exhibition that drew protests from the Nazis. One of the works from the exhibition was later chosen by Time Magazine for the cover of its edition that named Adolf Hitler as its "Man of the Year" for 1938 -- for good or evil.

The evil part came across in Von Ripper's depiction of a demented Hitler at the keyboard of a giant organ ,above which his murdered victims spin on a torture wheel. The caption for the cover read, "'From the unholy organist, a hymn of hate."

Only a few years later, Von Ripper was off to the Army, which trained him as a medical assistant, but he wrangled an assignment as a combat artist, first in North Africa and then in Italy. There, he met up with Pyle, who sought to describe his new friend and who would serve as his drinking buddy when Von Ripper wasn't volunteering to go on dangerous patrols.

"He swore lustily in English," and "he was as much at home discussing philosophy or political idealism, as he was describing the best way to take cover from a machine gun," Pyle wrote of Von Ripper in his 1944 book "Brave Men."

"It was hard to reconcile the artist and the soldier in Von Ripper, yet he was obviously professional at both. It may be that being a fine soldier made him a better artist. I couldn't conceive of his being rattled in a tight spot. He was so calm and bold in battle that he had become a legend."

Von Ripper's battlefield exploits caught the attention of Maj. Gen. William "Wild Bill" Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA. Donovan plucked him from the ranks and parachuted him into Austria, where he spent the rest of the war as a spy.

In 1944, the War Department put on an exhibit of combat art that included several works by Von Ripper. In the catalog for the exhibit, Von Ripper described how he viewed his work:

"A soldier-artist is a painter with a gun, a man to fight at times and to paint at other times. And in that he is very lucky: He can divert his effort from destruction, from killing, which is the soldier's job, to creative work, to build, make new things."

Pyle noted the impact the war was having on Von Ripper's combat art. In his paintings and drawings, Von Ripper's dead men "look awful, as dead men do. His live soldiers in foxholes have that spooky stare of exhaustion. His landscapes are sad and pitifully torn," Pyle wrote.

After the war, Von Ripper married a California woman, and they settled in Majorca, Spain, where he took up jewelry design, but again there was the hint of scandal. The Spanish government charged him with jewel smuggling, which his friends, including New York Times foreign correspondent C.L. Sulzberger, called bogus.

They said it was retaliation by the Franco regime for Von Ripper's role in the Spanish civil war. He was out on bail when he died of a heart attack at his home in Majorca at age 55.

His New York Times obituary called him a "courageous and colorful person who had justifiable reason to conduct an almost one-man campaign against the Germans. Time and again he led patrols against Nazi positions, and frequently he went out alone."

And the Army is now promising that one more piece of his legacy, the mural at Fort Bliss, will continue to live on.

-- Richard Sisk can be reached at Richard.Sisk@Military.com.

Related: Vet Who Kept Secrets of WWII 'Ghost Army' for 51 Years Honored