This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.

Fifty years ago, two-year-old Phan Kim Phuong was handed up into a military aircraft, her future a near-complete blank save one truth: She would not grow up in Vietnam. Saigon was falling to the North Vietnamese, people were scrambling to get out, and unbeknownst to the little girl, her family, her future, and her country were all about to be irrevocably altered.

“Her country” was about to become the United States, and Phuong was about to become Kim McNulty, an American girl growing up in an adoptive family in Pensacola, Florida, completely severed from her mother, community, and heritage.

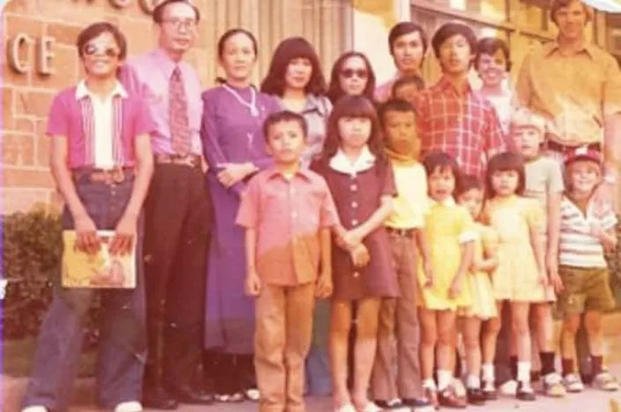

More than 3,000 children were evacuated from Vietnam in those final days, arriving in a country deeply divided from its involvement in the war. And yet many of them were welcomed by a host of Americans who wanted to help refugee families. Military members, church communities, and local residents provided shelter, meals, music—whatever they could to smooth the transition of lost, traumatized souls into citizens.

Now, half a century after the fall of Saigon, some of them are reconnecting.

Kim—now Kim Delevett—is one of the people reaching out to find others who share a piece of her history. Along the way she’s found the Air Force officer who ran the refugee camp she lived in, an aircraft maintainer whose hands may very well have been the ones that loaded her onto that C-130 plane, and others whose experiences have in some way overlapped with her own.

She’s planning a reunion at the site of the tent city in Florida where many of the Vietnamese refugees spent those first confused days and weeks in the U.S. before finding new homes, new families, new identities. She’s looking forward to sharing stories, to listening, to learning. But most of all she wants to say something to anyone who helped give her and other refugees a new beginning.

She wants to say thank you.

“It was all hands on deck,” Delevett said, “and if it weren’t for a community of folks who helped us, I wouldn’t be the person I am today.”

Praying the Teacher Didn’t Mention Vietnam

Delevett, who retired from a career with Southwest Airlines and lives with her husband and son in San Jose, California, is glad she has no memory of wartime Vietnam. She doesn’t have to recollect, as her older brother Lam does, the river beside his elementary school that reeked from dead bodies he saw floating down it.

She doesn’t have to relive the trauma of being loaded onto a hulking plane among throngs of desperate people and crying children, her mother waylaid on the clogged highways, as her children were carried off without her, never to be reunited.

She feels blessed that she doesn’t remember her earliest months in America. The weeks she held food tucked into her cheeks all day, unsure of when she’d be fed again. The nights she fell asleep with her hands sticking out of the crib rails, clutching Lam’s fingers, afraid to let go.

Delevett and her brother were placed with a former Navy pilot in a foster family that eventually adopted them. Home life was OK at first, but Delevett was teased terribly for the shape of her eyes, flat nose, and darker skin. She’d hide in the bathroom during sharing time at school so she wouldn’t have to talk about where she came from. She prayed that her eighth-grade civics teacher wouldn’t mention the Vietnam War.

Things improved in high school, where Delevett captained the cheerleading squad and was popular with her classmates. They twice voted her homecoming queen. But things were deteriorating at home.

“There was always just an unsteady uncomfortableness throughout most of my life,” Delevett said. “I've been really kind of hiding and masking a lot of pain, and a lot of insecurity, a lot of fear.”

When Delevett attended the Broadway musical Miss Saigon as a college student, she saw parts of her life story played out on stage. Vietnam had been a taboo—something to be ashamed of. Now she just felt incredibly sad to be so disconnected from it.

She decided to return to Vietnam for the first time in almost two decades. A hand-drawn map her older cousin had sketched by memory guided her to the house her cousins had lived in as children, where Delevett presented a letter of introduction she couldn’t even read.

She assumed her relatives were all dead. But the man living there read the letter and hurried her to a house where a woman called her Phuong and awoke an elderly man asleep on a couch. She soon realized the man was her uncle.

They both were in tears as the house filled with cheering neighbors and word spread that a long-lost relative had come home. The dramatic reunion became a gateway for reconnecting with a family, a country, and a past she had subconsciously longed for.

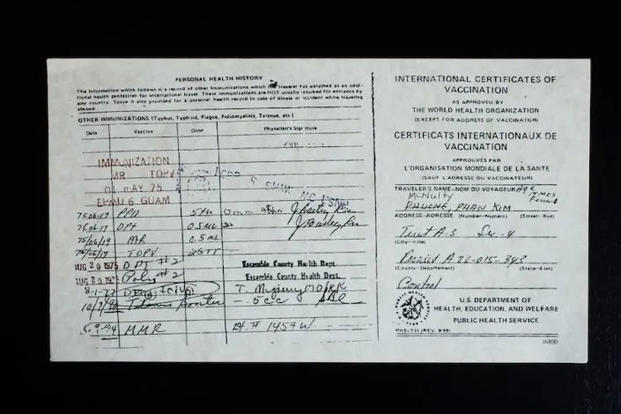

Delevett saw, for the first time, her own baby photos and heard her Vietnamese name spoken aloud. She found out her true birthday—June 28, 1972, not the date in October her teenage cousin had written on refugee documents in the camp.

And she found out the truth about what had happened to her mother.

Phan Thi Nuoi was supposed to be on the plane that carried her children across the world. An American contractor who employed Phan as a housekeeper had secured them all spots on a U.S. military transport. But Phan returned to her brother’s village to say goodbye and couldn’t make it back in time through the hordes of people trying to flee.

A photo taken six years later shows Phan smiling in front of a palm tree in a refugee camp in Malaysia. She had escaped Vietnam by boat and finally secured a visa to join her children in the United States.

Was it the jubilation of her anticipated reunion that overwhelmed her bruised and burdened heart? Phan suffered a heart attack and died the night before her flight.

It was devastating to hear. But finding her family, finding her homeland—it made Delevett want to find out more about her own journey and those who helped her along the way. And time was starting to run out.

The Air Force Colonel

In late spring of 1975, Ray Beery had been an Air Force colonel with command experience in Vietnam, sweating it out in the sticky panhandle air of Florida’s Eglin Air Force Base. As the U.S. mobilized a massive evacuation and resettlement effort, Beery helped set up and manage a tent city equipped to house, feed, and organize 6,000 refugees at a time.

“It was pretty chaotic, really. Things were all happening day by day,” said Beery, 94, who now lives in Leesburg, Virginia. Soon, plane after plane unloaded their human cargo, and Beery and a huge team of military personnel and locals met their needs.

Operation Timeline: The Trump Administration’s Impact on Veterans and the Military

One of those planes unloaded Delevett, Lam, and their cousins. Military spouses made sure unaccompanied kids like them were cared for; local kids showed up to play frisbee and soccer with the refugee children; a high school band performed.

After four weeks, the processing center had helped resettle around 10,000 Vietnamese refugees.

And until Delevett reached out in 2021 over Facebook, Beery had not heard from a single one of them.

Beery didn’t remember meeting Delevett as a toddler. It didn’t matter. Instantly, he was inviting her to join his family’s weekly check-in calls over Zoom. They talked for the first time, serendipitously, on June 28, the day Delevett calls her “Vietnam birthday.”

“It was so moving for me that he just accepted me,” Delevett said. “He actually called me his daughter. ... He was so proud of me and what I had done and accomplished, and he just immediately wanted me to be part of his family.”

Beery and Delevett’s instant connection makes sense to Dr. Robert Waldinger, a Harvard University psychiatrist who studies relationships and health.

“You’re at some high level dealing with hundreds or thousands of people, and then you get to meet somebody whose individual life you affected? That’s really powerful, right?” Waldinger said.

“If you shared a similar experience that most people don’t share, there’s an almost immediate bond.”

Beery started a Facebook group to connect with others who shared a piece of his and Delevett’s history. And for her part, Delevett made it her goal to give Beery that gift again and again; she would help him connect with as many people as possible who could show him that they appreciated him, appreciated this country, and had found success here. That his work had mattered to them as it mattered to her.

“I’m on a mission,” she said, “to thank as many veterans and volunteers [as possible] who helped us in 1975.”

The Aircraft Maintainer

Not long after meeting Beery, Delevett introduced herself on the Facebook page VietnamWarHistoryOrg and made a request: She was planning to write a memoir. She wondered if anyone in the group could fill in some details about the air evacuation from Saigon.

A man named Miguel Lechuga replied that he was part of an aircraft maintenance team supporting the evacuation aircraft in April 1975. “Thank you for sharing your story,” he wrote, “it brings joy to my soul.”

The pair spoke the next day for nearly an hour. She was riveted by his stories and photos from the final days and hours of U.S. engagement in Vietnam.

Like his memories of U.S. cargo planes loading passengers in the dark, since the North Vietnamese had begun bombing the flight line.

A C-130 catching fire after a rocket exploded under its wing tip, the crew egressing and later crawling through the grass, freaking Lechuga out as he heard the rustling sound and figured enemy forces had surrounded him.

A gunship falling out of the sky “like a dry leaf” after getting hit by a shoulder-fired missile.

The bodies of four people who had clung to the cargo doors of a C-130 falling like sacks of flour out of the sky as the plane rose.

“You never see the truth of what war really is like,” said Lechuga. “You don’t see the wounds. You don’t see the dismembered bodies. You don’t smell the blood, the gunpowder. You don’t hear the sounds.”

But some of the images that stuck with him were of the children. The ones he put into those planes, hoping for the best. The ones he called “precious cargo.”

“You’re doing a mission here so don’t get all teary-eyed or nothing, but to see the baby in a cardboard box getting aboard an airplane, you know, you’re kind of going like, man, I wish you luck,” Lechuga said. “I wish you the best, you know?”

Every now and then, after Vietnam, as he raised six kids in Wichita Falls, Texas, Lechuga would wonder how those other children were doing. What became of those precious kids?

“But you don’t know until you meet one,” he said, “and then it’s so rewarding.”

Meeting Delevett overwhelmed him. He felt a paternal sense of pride at her success, at the person she had become. As they sat in his car and talked in person for the first time, he cried.

The Little Boy Who Grew Up and Gave Back

Lechuga’s hands may have also lifted Wayne Bui onto a cargo plane bound for the Philippines. In April 1975, when he was nine years old, Bui was airlifted out of Saigon along with his parents, 10 of his siblings, and, he vividly remembers, an ungodly amount of Kentucky Fried Chicken.

The fast food had been donated by the spouses of American servicemen. And once the sickening jolts of the combat takeoff had ended and Bui slowly grew accustomed to the noise and the pressure of the C-130, the taste of KFC stopped his crying.

Bui made his way from the Philippines to Guam to Hawaii and finally to Minnesota with sponsorship from a Lutheran church. He grew up shivering through winter nights wearing a hat and mittens in a sleeping bag since the house donated to their family had no central heat. He got a paper route until he was old enough to work at McDonald’s, but his dream was always to follow in his older brother’s footsteps and become a paratrooper.

“At the same time, I wanted to join the military to kind of give back to what America had done for us,” Bui said. “To bring us over, give us a life, [and] the freedom that we enjoy.”

Bui joined the 18th Airborne Corps and jumped with the 82nd Airborne into Honduras for Operation Golden Pheasant. He served at the demilitarized zone in Korea and deployed to Kuwait, Afghanistan, and Iraq. After a 22-year career in the Army he continues to serve, through a Department of Defense job at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

In all his years of service, Bui hardly ever came across another who shared experiences of the fall of Saigon.

But once, when he was undergoing a routine military background check, the woman interviewing him was brought to tears by his story. Her father had been a pilot helping evacuate families from Saigon—maybe Bui’s—and he had just passed away.

“It was really an experience for both of us,” Bui said. “We both had tears, [she] gave me a hug and everything.”

It wasn’t his last connection to a U.S. service member from the fall of Saigon.

Bui’s boss at Fort Sill mentioned that his father-in-law had been an airman who worked on those planes. Maybe they’d like to meet.

The man’s father-in-law was retired Air Force Chief Master Sgt. Miguel Lechuga. When he came on post to meet Bui for the first time, Bui felt the same sense of serendipity and wonder—the same immediate bond.

“It was amazing, you know? Because some of the story that he shared, I share,” Bui said. “You feel like it was connection.”

Coming Together in Gratitude and Healing

More Vietnamese refugees and the Americans who helped them will be connecting soon; Delevett has used Beery’s Vietnam Refugees Eglin AFB Facebook group to make plans for around 40 families to meet at the site of the refugee center on May 4. It will be 50 years to the day from when Eglin welcomed its first planeload of refugees.

The reunion required special permission; besides being on base, the area is now used for missile testing.

Refugees, military personnel, and locals—they’ll stand in the place where their lives intersected and then diverged—lives that were changed immeasurably, or just a little, by the fall of Saigon.

“I know pain and loss from the war,” Delevett said. “I lost my mother and miss her every day. But I’m already witnessing the loss that our children and grandchildren are experiencing when we don’t share our stories. Our stories are an important part of American history, and families need deep connection.”

Standing back on this spot, she’ll marvel at the passage of time, and the twists of life. And Delevett is probably not the only one who will say a silent prayer of thanks: that she found her way, and that she found her way back.

This War Horse story was edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.

Editors Note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.