"Things have changed."

Lt. Col. Phillip Mason stood on a narrow peninsula in early April just west of downtown San Diego, overlooking the coastal border between the U.S. and Mexico as a seasonal fog obscured the view.

Mason, peering through wraparound-style sunglasses, had been tasked with a border mission before, back in 2018. This time, he is serving as the commander of Task Force 716, composed of 350 soldiers who are helping Customs and Border Protection by keeping a 24/7 eye on the Pacific Ocean looking for migrants and smugglers.

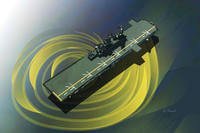

To cut through the fog, the soldiers have hauled in a Ground-Based Operational Surveillance System, or G-BOSS, set up on a trailer from Kentucky. The platform uses infrared optics among other tools to pierce through visual obstructions, like the omnipresent mist.

Read Next: 'Everything Is on the Table': Army Eyeing Expansion of Privatized Barracks

"This is a great example of what has changed," Mason said, gesturing to the platform. Its maker had pitched it to the U.S. military by saying it would "save lives" and help troops "detect the enemy's movements at great distances, allowing for rapid response to threats." Soldiers in the task force said the system has helped them see speedy jet skis, recreational vessels and skiff-like "panga" boats likely being used to drop off people or contraband into the U.S. from Mexico.

For years, U.S. troops have been sent to the border to assist law enforcement agencies in a supporting role -- mending fences and detection.

But the soldiers with Mason represent just a small portion of the roughly 10,000 troops deployed to the U.S.-Mexico border over the last three months amid President Donald Trump's immigration crackdown, in which military assets and personnel are increasingly being relied upon for a new type of mission.

Other units have repatriated migrants off U.S. soil via military flights or have held them in Pentagon-owned detention facilities like the ones at Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, as part of the deportation aspect of the administration's aims.

Military.com spent two days earlier this month observing and talking to nearly two dozen soldiers and Marines deployed to the border near San Diego, one of the only places along the nearly 2,000-mile-long stretch of land separating the two countries where both services are positioned en masse.

The differences Military.com observed, and heard about, in comparison to past border missions were both stark and subtly important. Some of the equipment brought to the border was primarily used during the last 20 years of war overseas, and the mindsets of the troops who operate them reflect that of those on a dedicated operational deployment.

That deployment mindset parallels the perception that the Trump administration is hoping to portray about this mission -- "border security is national security." On the campaign trail, Trump consistently referred to those crossing the border as an "invasion," a sentiment repeated by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth during visits to the border in recent months.

"From the Defense Department, we've watched for a couple of decades other people's borders being secured while ours was open for an invasion of drugs and of violence and of chaos for American communities," Hegseth said in early March.

The risks, both real and potentially overhyped, are often on the minds of troops here with no known end date to their mission in sight. Those perceived dangers often stand in stark contrast to the glaring reality of being deployed within the contiguous United States, especially near a major metropolitan city with all of the trappings of familiar Americana.

The combination has resulted in troops living two contrasting lives -- undertaking armed patrols of the border wall, looking for signs of cartel members and migrants amid reports of nebulous drone incursions one moment, then shifting to relaxing at San Diego's Imperial Beach or grilling out at one of the many hotels where they are staying the next.

"That's the weird part," Mason said, when fielding a question about how troops here are communicating with their family members back home. "This is a deployment. We deployed, but we're still in the United States -- I equate it to the end of, the height of Iraq and Afghanistan, where we had really good comms structure in place."

Two veterans of previous border missions said they didn't view their participation in those first operations as deployments, with one describing it as a "vacation," citing limitations on what they were actually able to do there and adding that it was a "waste of taxpayer dollars." Both veterans were granted anonymity to speak candidly to avoid professional repercussions.

Active-duty troops deployed to the border during Trump's first term could not move from static observation posts; used mostly Border Patrol equipment, such as cameras and trucks; and were armed with a limited number of pistols with stringent rules around their storage and use in an effort to mitigate the legal realities of deploying active-duty troops within the U.S.

"We're protecting our nation's borders. We're securing the barrier. We're assisting Customs and Border Protection," Mason said. "But that's about the end of the similarities, because the terrain is different, the threat is different, the illegal alien that may be coming across is different. The cartels are different."

Now, troops are also armed with rifles, fitted in full kit for foot patrols along miles-long stretches of barrier wall. Marines, though not doing foot patrols, have taken to "Guardian Angel" details, in which a team of roughly four are charged with protecting their counterparts as Marines reinforce the border wall. In other states, soldiers ride in eight-wheeled armored personnel carriers for patrols. Equipment like the G-BOSS is new too, and units are requesting more of it.

"There's a different threat that the soldier faces," Mason said. "And then a different solution set that we have to put in place to ensure that we're doing that job of protecting our borders."

Optics

Though much has changed about the border mission, one thing remains from past efforts: There's a lot of watching.

Elsewhere on the border, Spc. Marcelo Reid-Celis peered through a pair of binoculars at the border wall separating the United States and Mexico on one of the two detection and monitoring sites his platoon operates near San Diego.

There's a sharp, visible contrast between the two countries: The U.S. side, near Goat Canyon, shows miles of seemingly endless green shrubbery, while the outskirts of Mexican city Tijuana beep and bustle away in the early afternoon.

Two soldiers working in eight-hour shifts keep an eye out for migrant crossings and suspected cartel activity amid the hubbub of two major cities populated by millions of people. The soldiers have dubbed this site "bunkers," referencing a network of dugouts across San Diego once meant for coastal defense during World War II.

In recent weeks, the Army has added armed foot patrols to its border mission. Here in San Diego, soldiers in teams of four walk along the border wall on the U.S. side, humping their gear three-quarters of a mile down an access road and then back again.

They are armed with M4 rifles equipped with an Advanced Combat Optical Gunsight, or ACOG, as well as binoculars and a thermal weapon sight.

What are they looking for?

"Anything that looks out of the ordinary," said Sgt. DeAndre Swinson, a soldier assigned to Task Force 716 who has been on two of these patrols, though it was unclear what would count as noteworthy for these troops.

On patrols, soldiers report via radio anything they deem suspicious to nearby Border Patrol agents -- who, what, where, when and, as much as they can tell, why, Swinson said. The agents then assume the law enforcement role of apprehending those attempting to cross the threshold, something the military was not allowed to do at the time of Military.com's visit.

There is a common understanding among service members on this operation that an important part of the mission is about optics. Troops are broadcasting to potential border crossers and alleged cartel members that there is an earnest military presence here, clearly visible in the form of robust military hardware, ready to defend itself and the nation, including through allusions to lethal means.

"Sometimes, it is just to be seen, send a message, the image piece of it," Mason, the commander, said, adding that the patrols also offer soldiers a better idea of what's happening close to the barrier, where they can see whether a ladder was left up on the wall or parts of the concertina wire were cut.

That information gathered by soldiers on these patrols is then turned over to Border Patrol to inform its intelligence arm.

There have been multiple prongs to the Trump administration's efforts to deter migrants from attempting to cross the border -- the administration's deportation of immigrants and, in at least one case, the mistaken expulsion of a Maryland resident to the CECOT maximum security prison in El Salvador known for its human rights abuses; stepped-up raids in U.S. cities; and the increased military presence at the border. Collectively, they have had a clear effect on crossings.

In April of last year, there had been 185,466 apprehensions to date for 2024, according to agent Oscar Lopez, a spokesperson for the U.S. Border Patrol's San Diego Sector. There have been only 44,084 at the same point this year.

Service members expressed a very positive outlook about their mission near San Diego. Many of them said they felt fulfilled in being able to defend the contiguous territorial integrity of the country and that being able to do the jobs they generally signed up for in the military -- such as engineering -- added to that feeling, especially in contrast to the repetition of garrison life.

"I like it better than being in garrison. Garrison is a lot of simple tasks like going to the motor pool or check[ing] the vehicles or clean[ing] the company," said Spc. Dalton Emanis, with Task Force 716 and of Athens, Texas. "So finally getting the call to go and do something makes [me] feel like I'm here for a reason."

Out the Door

Within days of Trump's inauguration on Jan. 20, the first batch of roughly 1,500 active-duty troops, including many Military.com spent time with, were rapidly deployed to the border from units across the country.

As U.S. Northern Command grappled to develop a solid plan on what one official described as an "aggressive timeline" -- just 30 days from the president's Day One order for the Pentagon to deploy troops to "ensure complete operational control" of the border -- some troops began boarding C-17 Globemaster III aircraft within hours of being notified.

On the ground, those preparations included quickly packing personal gear and equipment, then boarding trucks or planes to get to places like San Diego. Behind the scenes, a complicated labyrinth of tasks took place to ensure that troops' home life was well-prepared for a rapid deployment with no known end date.

"When we're rapidly removed like that, there's a lot of effects that come out of it, like family, life in general, personal stuff," 1st Lt. Tristan Rothe, a platoon leader with the 549th Military Police company out of Georgia, said while describing the settling-in process for troops.

Locking up barracks rooms and securing personal vehicles, some of which were parked in storage lots, lent to a friend, sold or even left in the unit parking lot, were all part of getting out the door, according to the troops at the border.

It is not clear to service members on the ground when their part of this mission will be over, with some initially believing it would last roughly a month. Nearly three months later, that has proven to be untrue as leaders work to be as transparent as possible with their troops' expectations.

"It is up in the air in that we don't have a defined redeployment date at this time," said Mason, the Army task force commander in San Diego. "However, most of us have been doing it long enough, we're planning for a nine-month deployment down here."

Recently, Trump issued a memo handing over a narrow stretch of federal land known as the Roosevelt Reservation to the Pentagon -- the results of which have yet to take full form, though the move prompted concern from legal experts who said it would open the possibility of troops taking on the responsibility of apprehending migrants, something they were prohibited from doing during Military.com's visit.

Days after the memo was issued, NORTHCOM announced that troops in New Mexico could now temporarily detain, search and conduct crowd control against "trespassers" who find themselves in the military-controlled area -- one of the most recent among numerous changes that service members have had to react to in the ever-evolving mission three months after its launch.

Rules for the Use of Force

While pictures and video of military hardware at work at the border have been blasted out on social media by administration officials, imagery consistent with operating in war zones against an armed enemy, the risks troops have encountered thus far mirror military exercises, but with an added sense of uncertainty.

Earlier this month, just days after Military.com's visit, two combat engineer Marines from Camp Pendleton were killed after a vehicle accident during a convoy near Santa Teresa, New Mexico, marking the first known deaths associated with this border mission. A third was injured and was in critical condition at a local medical facility.

A Navy corpsman, HM3 Makhel Herd, who is from San Diego, told Military.com that injuries he might see to Marines reinforcing the barrier include lacerations from the concertina wire, musculoskeletal trauma as a result of falls, and heat casualties as they work throughout the day in the sun.

However, there is also the perceived threat of cartels operating in the shadows. Troops said they monitor the area via foot patrols and stationary observation posts, though there had been no reports of direct confrontation at the time of Military.com's visit. Lopez, the Border Patrol spokesperson, said that there are three cartels operating in the San Diego area: Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generacion, Sinaloa Cartel and the Tijuana Cartel.

"These cartels leverage local gangs/smugglers and charge them a tax to operate in these areas. In turn, the local gangs collect fees from migrants looking to cross the border illegally," Lopez said. "The vast majority of migrants that crossed the border illegally pay fees. The smugglers and gangs have historically patrolled their own areas to enforce the collection of these fees."

The administration has designated cartels as foreign terrorist organizations, which legally opens the aperture on how it can combat them. Top administration officials have not been shy about hinting about targeting those groups with potential strikes within Mexico.

Service members around San Diego have been instructed that they are allowed to defend themselves through lethal means, as evidenced by cards they carry that bear the standing rules for the use of force, commonly known as SRUF, and assurances from top Pentagon officials.

There is also a level of secrecy here applied under the umbrella of operational security. Service members are allowed to use social media "as they would with any major exercise and/or deployment," said 1st Lt. Giselle Cancino, a public affairs officer assigned to the Marines' Task Force Sapper, another newly formed unit composed of about 500 Marines and sailors from Camp Pendleton. But they must abide by some constraints.

Troop complaints are virtually nonexistent in their usual pockets of social media, and some service members described having to keep details of their deployment -- like specific locations, movements, dates and activities -- ambiguous in communications with their families, at least in the beginning.

While soldiers said that they haven't had any face-to-face interactions with suspected cartel members or migrants, for that matter, the signs are there, they said: a suspicious house identified by the Border Patrol as a cartel location, someone looking through binoculars at their positions or even buzzing drones they said could be used to surveil their activities or drop off drugs into the U.S.

"It could be reconnaissance for the cartel. It could be a device used to transport drugs across the border," Mason, the Army task force commander, said of the drones. "It could just be a personally used drone. Unfortunately, there's no way to know, which I think is the scariest part of that."

Gym, Tan, Liberty

Service members deployed to San Diego enjoy several privileges and freedoms that they would not otherwise be afforded on other missions. In their off time, between hard work on their shifts or after designated "training days" when they take care of necessary requirements such as physical tests, service members said they frequently go to local commercial gyms, beaches and restaurants or participate in group morale events.

"There's always those homebodies that want to stay in their hotel room and be just a couch potato," said 2nd Lt. Carlos Gomez, a platoon leader assigned to Task Force 716.

"That's not the idea we want to promote," he said, adding that his team recently went go-carting and to museums around town.

Troops are allowed to take limited leave or liberty within a certain radius, a coveted chance to visit family, friends or take time off so long as it does not interfere with their shifts. They can also drink alcohol (two drinks for soldiers, four for Marines), which is limited to eight hours before the start of the workday and was also restricted in the early days of their deployment.

For several days at the beginning of the deployment, Marines were roughing it in tents along the border. Since then, the military has contracted swaths of hotels across San Diego, many of which have hot tubs, breakfast and regular cleaning services.

The Marines, who are based out of Camp Pendleton, which is less than an hour drive from downtown San Diego, have the unique ability to drive back home to visit family or take care of home-station tasks.

"The one great aspect about this is we're not far from home, so even though we are deployed, we are still here in the local area," said 2nd Lt. Sabrina Basel, a Marine platoon commander and engineer officer from Long Island, New York. "And if Marines need accommodations, we can get them back to Camp Pendleton on our off days or on our training days.

"It definitely is unique compared to most deployments that these guys are used to," she added.

While the Marines are on shift reinforcing the barrier wall, a post exchange truck or "roach-coach" comes about twice a week to drop off vapes, snacks and Zyn, the popular nicotine pouch loved by troops, which is sold to them here at base prices, rather than the elevated costs tied to state regulations elsewhere in California.

"We don't really need or want for anything," Marine Staff Sgt. Ian Duba, a platoon sergeant, said. "Anything that we could have, it's just a quick 'route that up' and we typically get it in 72 or less hours."

Some things that military leaders are often hyper-aware of in deployment environments, especially ones as unique as the border mission, are boredom and burnout management that, left unchecked, can result in discipline issues and poor morale. Operation Lone Star, a border mission headed by the Texas National Guard, was rife with suicides, pay issues, low morale and, eventually, restrictions on privileges.

Military.com asked whether the task forces experienced any disciplinary issues here and, while leaders were reticent to offer specifics or confirmation, the publication could find no evidence of publicly identified cases in San Diego.

The Naval Criminal Investigative Service said that it had not initiated any investigations into criminal misconduct involving troops at the border this year. The Army's Criminal Investigation Division said that it is investigating reports of "felony-level misconduct" involving soldiers at the border, but would not offer specifics and did not reply when asked whether those investigations pertained to the San Diego area. The San Diego Police Department declined to comment "on anything related to military operations at the border and their effects on the communities in the area."

Leaders said that some venues within the area are blacklisted, largely informed by existing policies at established military bases in San Diego, as well as through input from local law enforcement.

"This is like any other metropolitan area in America, and so there are certain things that the American people are allowed to do, but we as U.S. Marines and sailors by UCMJ are not allowed to do," said Lt. Col. Tyrone Barrion, the commanding officer of Task Force Sapper. "I can't control what the American people do. That's the freedom of being here in America. But we hold ourselves to a higher standard."

No Man's Land

In a narrow stretch of land between the U.S. and Mexico, Marines are hard at work welding and attaching concertina wire to high barrier walls that separate the two countries. Other Marines, part of a Guardian Angel force keeping watch, stand close by as their counterparts work, armed with rifles, magazines loaded but no round in the chamber as they scour the border for threats that may harm their peers.

While still part of America, the Marines have dubbed this dusty strip "no man's land" because "there should be no people here besides U.S. Border Patrol and obviously ourselves working in here," Barrion said.

Trailers rented by the Marines and a massive construction boom roll through the dust as military engineers don respirators and welding masks to repair and improve one of the key facets of the administration's effort to secure the border: the wall.

Marines requisition a steady stream of materials used to reinforce the barrier and apply it to the wall.

"Our aim is to have this obstacle in place so folks do not try to attempt to enter this country illegally, and so that's the purpose of it," Barrion said. "It's not there to injure anybody, maim anybody. It's there to act as a barrier to funnel folks into America legally and have a secure border, as the president wants."

Marines were deployed here to reinforce barriers during Trump's first term, but they were not armed with the long guns their Guardian Angels carry now, NPR reported. An old policy from the very unit these Marines come from said Guardian Angels must watch over their units' security with an "ambush mentality."

Just a short drive from where the Marines are toiling away on the wall, there’s a half-acre park near the ocean spanning the border that was once meant to foster binational solidarity. It is closed, and the addition of freshly laid concertina wire has sunk the hopes of the park's supporters dreaming of its return.

Friendship Park was inaugurated in 1971 by then-first lady Pat Nixon with promises of surfing; swimming; planting trees and flowers; "many happy times;" and visitation between the two countries in the name of unity.

"May there never be a wall between these two great nations," she said. "Only friendship."

Since then, the park -- once the only federally established place along the border where people from the two countries, and those awaiting legal status, could meet freely -- has proven to be a symbolic representation of America's long-evolving relationship with its southern neighbor.

Over the last several decades and as illegal immigration fears proliferated in America, U.S. officials have implemented additional restrictions at the park, slowly reducing visiting hours, allowing only a certain number of people into the space at a time, installing dense mesh that limited patrons to "pinky kisses" with loved ones through the barrier, and eventually installing 30-foot high walls.

Around 2007, supporters planted a circular garden that stretched across both sides of the park. In 2020, U.S. officials uprooted it, according to Dan Watman, a program director for the Friends of Friendship Park.

In recent weeks, Marines laid down concertina wire at the park "right through the area where the garden is supposed to go," he said, ignoring past assurances from local U.S. officials that it could come back.

"It's disheartening," said Watman, who now lives in Tijuana and has been in the area for decades. "I've dedicated my life to this space and to the idea of cross border friendship, because I really feel like a vital part of keeping us safe is being able to know each other and trust each other."

Having been on the Mexico side of the border since 2009, Watman said that the additional presence of troops in the area has been met with "bewilderment" there and that this recent deployment constituted the "most amount of enforcement" he's seen at the border in 20 years.

He worries that a hyper-focus on perceived dangers by U.S. troops could result in violence, accidental or otherwise.

"I'm not saying for sure it's going to happen, and I hope it doesn't," Watman said. "But there is that potential."

On an overcast day last month, Watman approached the Marines installing the concertina wire on the U.S. side of Friendship Park, as recorded in a video he shared with Military.com. He asked a Marine whether they would skip this section of the wall to allow supporters to replant the garden they had been promised.

"This wire is temporary and removable, and it's at the request of Border Patrol," the unidentified Marine said, speaking to Watman across the threshold between the two countries. "I don't really have control over whether I do it or not, I'm just doing what they request."

The Marine continued, "We're just trying to keep the bad stuff from coming across.

"I only have so much pull before they just tell me to do what I have to do and shut up and color."

Related: Military to Take Over Federal Land Along Border Under New Trump Order