The opinions expressed in this op-ed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Military.com. If you would like to submit your own commentary, please send your article to opinions@military.com for consideration.

In 2003, I discovered that a friend claimed he had been called "bloodthirsty, civilian-killing scum" in an airport after returning from 1991's Desert Storm.

I was the one who picked him up at the airport in 1991. He didn't mention this interaction at the time.

My friend had claimed to have served in Desert Storm in Iraq in the 82nd Airborne Division.

He deployed to Kuwait in May 1991. Desert Storm had ended. The 82nd had departed. I had picked him up at the airport that September. I was the one who served in Desert Storm in Iraq with the 82nd Airborne Division.

I discovered that he claimed to have earned a Purple Heart in Somalia, and upon his return, he claimed to have been called a racist child-killer.

He didn't go to Somalia. He had been stationed in South Korea, where he met his first wife. I attended their wedding.

The Purple Heart lie was nefarious, but he didn't gain anything that I could tell -- just narrated some vanity project. The wannabe producer was pleased to use a combat-wounded veteran. My friend was only a voice, so what's it matter? I did send him an email: "A Purple Heart in Somalia? Not cool, dude." I didn't want a reply. I wanted him to know I knew.

I wanted him to feel that shiver up the spine we all feel, that I've felt, when our awkward lies are revealed.

I had met my friend during the last months of the Cold War. We shared a sense of sarcastic humor and appreciated the Army's silliness. We went separate ways, paths crossing here and there. I left the Army; he stayed active for a few years longer.

It was difficult, keeping in close touch with Army friends during the 1990s and early 2000s. No social media -- only phone calls, emails, maybe a wedding, for gossip through the grapevine. Years passed; Iraq came around again.

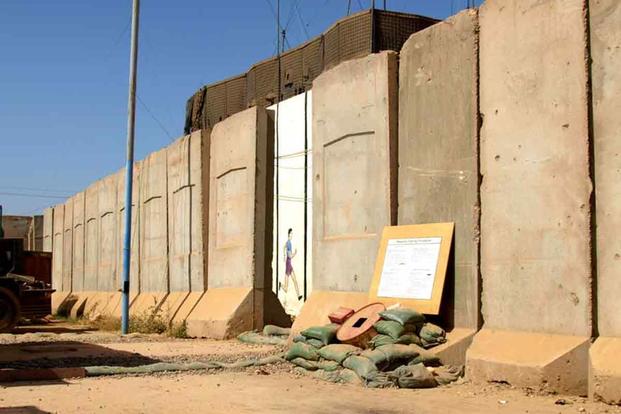

In 2008, it was his turn to pick me up at an airport. We met at Baghdad International (BIAP), so there was no doubt he was in Iraq this time. He had volunteered through his Army reserve unit. He toured me around Camp Victory before dropping me at the Striker Stables where I'd meet the Rhino for the Route Irish convoy en route to the Combined Press Information Center and my reporting embed with the 25th Infantry Division.

He showed me the spot at BIAP where Sgt. 1st Class Paul Smith's 2003 actions had earned a posthumous Medal of Honor. In 2008, the site was plywood and dirt. Without my friend to identify its significance, there was no evidence of any valor.

My friend had always cared about these sorts of heroic places. I'm nostalgic in different ways.

By then, I knew my friend had tried to steal some valor for his own. But since he had made it to wartime Iraq for real, it all worked out.

I wanted him to kill time with me, while I waited at the stables for the midnight Rhino ride. He said he had a meeting and he'd try to make it back, but he didn't seem that interested. I was a little put out; old friends don't meet up in Baghdad that often. I expected to be more of a priority.

So I sat alone in the stables until one of the contractor-types yelled that a Rhino was on the way. I continued my journey to Tarmiyah and the 25th Infantry. But that's a different story.

My friend and I became estranged in 2010. He had leaned into Tea Party conspiracies, posted some rant to my Facebook -- called me ignorant, naïve, said I'd been seduced by Obama's socialist charisma. Some screed attacking my character.

I acted in anger. Told him to take his tired bullshit somewhere else, "defriended" him in a huff. Regretted it later, but I don't often demean myself by "refriending" anybody.

Thus concluded the relationship.

In that same Facebook thread -- maybe I was endorsing something treasonous like a tax to fund universal health care -- were critical but less-strident comments from a lieutenant I had met in Tarmiyah, a platoon leader with the unit I had embedded with after my friend ditched me at the Striker Stables. So it's the same story after all.

The lieutenant had earned a Purple Heart in a bombing that occurred not long after I had left Tarmiyah. The lieutenant shared my friend's politics, but his more reasonable disagreement didn't wind me up the same way. Maybe since he had earned a Purple Heart, he deserved some leeway. Or maybe he wasn't a real friend, just a memory from a Tarmiyah outpost, so I had no emotional investment, no expectations.

What I didn't do -- as I simmered in social media's impotent anger -- was what I thought long and hard about doing: Two people think I'm a naïve rube; one of them earned a Purple Heart; now I can unleash the long-hidden, long-buried, long-lurking revelation that the other lied about earning a Purple Heart.

Who's the rube now? Did you think I would give you the last word? In all the ways I've acted through the years, whatever gave you that idea?

The nuclear option's moment had arrived, the most mean-spirited escalation to exploit that perfect confluence: Valor meets venality.

I thought long enough to not write that comeuppance.

Whose valor could I have exploited? Not mine. Not my friend's. He had only jealousy, for an 82nd Airborne combat patch, or a purple ribbon, some birthright he must have felt denied -- even in Iraq, trying to latch on to Paul Smith, like I should care where a better man than us had fought and died.

Whose valor could I have stolen, for my own purposes?

The lieutenant's, of course -- I could have stolen his valor for a bitter insult, used his real Purple Heart to mock a fake one. I could have smeared the lieutenant's blood onto my friend's face, but I'd be -- am? -- the one with bloody hands.

Ten years ago, my thoughts weren't that deep, though a version of that concern crossed my mind. I did the simplest thing, what I had done before, what I would do again, and cut the cord.

My friend is still out there, still claiming in message board arguments that he had served in Desert Storm in the 82nd Airborne, one-upping other blowhards. He went to Iraq three times from 2004 to 2009. The one time he didn't go was 1991. Why would he need to claim even my tiny war? That insignificant skirmish? He'd already claimed a Purple Heart -- did he need Grenada? Panama?

I've lied by omission. I've been asked if I killed anybody. Sometimes I didn't confirm or deny, just said something melodramatic like, "Those were bad days." Anyway, nobody brings up Desert Storm anymore.

Today, I share the modern veteran's tendency toward cynicism and making sure everybody knows that whatever war we fought in was for bad reasons, under bad leaders, with bad results. Or the other way -- that entitled puffery -- that our service means we know better, that we are better. Whatever emotion we feel, damn, we make sure you know it. Get angry, bring up Pat Tillman to make some antiwar point, or get patriotic, bring up Paul Smith so people know you remember; aren't you stealing valor in a different way? The first casualty of war isn't innocence, it's perspective.

Toward my friend, I felt -- feel -- embarrassed, like I found his porn collection of some self-loathing kink. Whatever gets you through the day, but I don't want to know about it. In this squeezing, grasping era, stolen valor seems so grubby -- stolen for what? To impress who?

I once ordered a free Veterans Day pizza and the waitress asked to see my DD-214. I was glad. Finally, somebody who didn't trust me, thinking I was trying to scam stolen-valor pepperoni.

Maybe some grifter fooled that waitress before, and now, hell no, she's not giving out more free pizza without proof. Stolen valor always bubbles up from those pathetic stories, those greasy anecdotes.

In the early 1990s, my Army Reserve training was at Fort Benning at the same time my friend graduated Airborne School. He had always wanted to be a paratrooper. I took his picture as he walked off the drop zone, earning his wings after the fifth jump. My combat patch has a tab, so I fit in even with no wings on my uniform.

No wings? That's right. I am a hypocrite, with this story. I went to Iraq "with" the 82nd Airborne, not "in" the 82nd. I never went to Airborne School, was attached to the 82nd through a subordinate unit. I always use the "with" preposition.

It's not my fault if people don't understand language's distinctions.

Back at the barracks after my friend's final jump, another new paratrooper, a tall attractive woman, made some small talk with us. After she walked away, my friend regaled me with a story of hooking up with her, how she was a "tall drink of hot legs."

Her manner did not resemble anyone who saw my friend as more than one guy among many. I knew his claim was a lie from the moment it left his mouth. It was funny. He laughed. I laughed. We both laughed. Not my reputation he was slandering.

Editors Note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter