The biggest problem with commissaries, and perhaps a major reason why sales are falling, “is product availability,” wrote Vicky Olhson, wife of a retired Air Force officer who shops on Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Ala. “There seems to be a total lack of concern on the part of the commissary management to keep shelves stocked.”

Many commissary patrons echoed this complaint in reacting to our recent news column on base stores and it’s not news to the interim director of the Defense Commissary Agency, retired Navy Rear Adm. Robert Bianchi.

In an interview, Bianchi said he is committed to reforming over the next year how commissary shelves are stocked.

“The main message I would hope you can get across to [shoppers] is, ‘Hey, I get it. I know there are problems and I’m trying to attack them,” said Bianchi.

He isn’t sure himself how widespread is the problem of empty shelves across the commissary system, Bianchi said. But it is a problem, reflected both in patron satisfaction surveys and in direct feedback from shoppers Bianchi heard during visits to 15 stores since becoming interim DECA director last November. [He also remains chief executive officer of the Navy Exchange Service Command.]

“The only place you can sell air is at a gas station,” Bianchi quipped. “If it’s not on the shelf, we can’t sell it and, of course, that leads to patron dissatisfaction.”

An American Customer Satisfaction Index survey of commissary patrons conducted last year asked what issue they most recently complained about. Freshness and quality of produce was number one; Bianchi said that, too, is an issue he’s addressing. But product availability, or empty shelves, was the second most frequent complaint, cited by 17 percent of respondents, he said.

Unlike retail grocers, commissaries aren’t staffed to stock shelves. For about half of all products sold, managers sign “commercial activities” contracts with firms that provide stockers. Because performance is monitored, these contracts generally work well, Bianchi said.

Complaints about empty shelves are tied to a separate, unconventional arrangement for stocking brand name goods. Vendors for national brands are responsible for putting products on shelves. They, in turn, use third-party service companies that hire stockers to work in stores after hours solely on these products.

DeCA has allowed this arrangement for decades despite obvious weaknesses including lack of management control over the performance of these workers. Firms that supply vendor stockers don’t supervise them, Bianchi said. The big ones are Top Gun and Prime Team and mostly they ensure that stockers are paid.

If stockers don’t show, product isn’t put on shelves. If they show but can’t access products, for example if pallets of other goods are in the way, some of them leave without stocking that product, Bianchi said.

“If you’re scratching your head a little bit now, I don’t blame you,” he said. “When I first came on to this whole thing, it kind of hurt my head. It’s so different from what we do on my NEXCOM side where the store team is the team, and you say, ‘Sally or Johnny needs to go grab stuff out of the back room’ and they do it.”

“There are situations where people have said, ‘I’m not going to move all that stuff out of the way to get to my stuff.’ I know it seems kind of hard to believe but these are episodes…relayed to me by my store leadership,” Bianchi said.

He added: “I don’t want to malign all of them because we have some stores where vendor stockers are working and the relationship is very good.”

Some vendor stockers are even military spouses or service members who elect to work part time to earn extra income. But Bianchi has concluded that vendor stocking is unreliable and an “unsustainable model” for keeping shelves full.

Managers and patrons are right to feel frustrated, Bianchi said. “And frankly, because we’re paying for this service in the cost of goods being charged in our negotiations with manufacturers, I’m not getting my money’s worth.”

Bianchi said he doesn’t know the full history of how this evolved over time.

“All I know is, right now, I’ve got patrons in certain places telling me they’re dissatisfied. I have store leadership telling me they have issues. And I want to make things better. I’m looking at positive alternatives.”

One alternative he began testing May 14 at the commissary on Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek, Va., is to hire exchange employees to stock brand name goods. He also directed affected vendors to tally what costs they had been passing on for stocking services and lower brand product prices accordingly.

The new arrangement won’t trigger additional savings for shoppers; the commissary will use price cuts to help pay exchange workers stocking shelves. But shoppers will see fuller shelves, Bianchi said.

Some exchange workers will begin to restock the Little Creek commissary during the day, rather than only when stores are closed or when managers are pressed to use their own employees to keep popular brands on shelves.

Early results at Little Creek have been “glowing,” Bianchi said.

“The folks are showing up. They’re supervised. You can imagine how much easier this is now,” he said. “You send the team into the back and say, ‘Everything along that wall needs to get onto the floor” as opposed to seeing stockers looking for particular products they alone can handle.

Companies involved in vendor stocking obviously are concerned by the Little Creek pilot, Bianchi said. If they propose a better model, he’ll consider it.

Patrons don’t care how a product gets to the shelf, Bianchi said. But when it is not there, stores lose sales and shoppers get upset. They’d be more upset to know that, “more than likely, there is probably product in the back and just nobody there to bring it forward. And that’s very disturbing to me.”

Bianchi isn’t ruling out other solutions, including hiring more commissary staff. At most commissaries, employees are represented by unions. Bianchi said he is asking the unions to agree to add shelf stocking to the type of work clerks can do. This is to give managers greater flexibility to set work schedules if he does decide it would be cost efficient to hire more store employees to stock shelves.

A separate problem impacting product availability is disappointing “fill rates” by suppliers, Bianchi said. Commissaries are getting all the product they order only 89 percent of the time. Bianchi said that’s unacceptable. He wants the fill rate raised to at least the 98 percent set for Navy exchanges.

The commissary chief said he delivered these messages to about 150 vendors, brokers and brand-name manufacturers attending a meeting of the American Logistics Association in Richmond, Va., May 16.

Bianchi said his strategy to end the empty shelf problem is “crawl, walk, run,” so that when he’s confident he has the right solution, or combination of solutions, he’ll implement swiftly in the year ahead. In that regard, Bianchi acknowledged he is in talks with senior Defense officials to lengthen his tour as interim DECA director, which otherwise would end in June.

“I’m committed to hanging in there because I believe in these benefits and I think we’re making important progress,” Bianchi said.

To comment, write Military Update, P.O. Box 231111, Centreville, VA, 20120 or email milupdate@aol.com or twitter: @Military_Update.

|

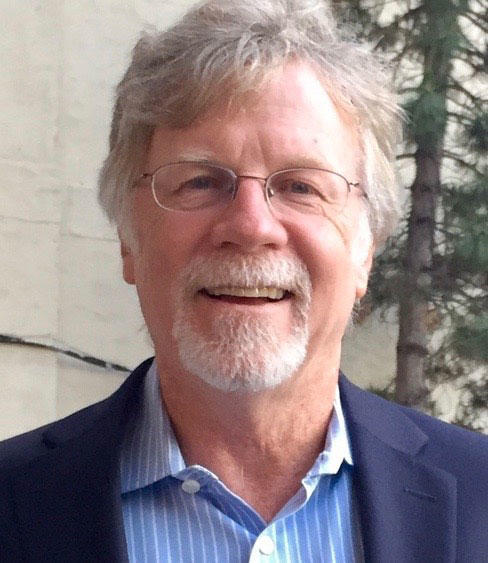

Tom Philpott has been breaking news for and about military people since 1977. After service in the Coast Guard, and 17 years as a reporter and senior editor with Army Times Publishing Company, Tom launched "Military Update," his syndicated weekly news column, in 1994. "Military Update" features timely news and analysis on issues affecting active duty members, reservists, retirees and their families. Tom's freelance articles have appeared in numerous magazines including The New Yorker, Reader's Digest and Washingtonian. |

|

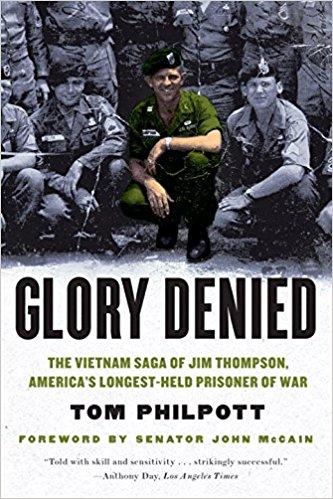

His critically-acclaimed book, Glory Denied, on the extraordinary ordeal and heroism of Col. Floyd "Jim" Thompson, the longest-held prisoner of war in American history, is available in hardcover and paperback on Amazon. |