Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps personnel chiefs jointly testified in January before the Senate armed services subcommittee on personnel on the need to make targeted reforms to the 1980 Defense Officer Personnel Management Act (DOPMA) to provide greater flexibility to recruit and retain the officers they need.

DOPMA reforms unveiled Wednesday by the full committee, in its version of the fiscal 2019 defense authorization bill (S 2987), might be viewed by service leaders as having gone beyond what’s needed to modernize officer management.

One provision likely viewed as radical would mandate that the services end the practice of defining promotion zones based on officer “year groups” – the date officers were commissioned or gained current rank – to rely instead on competitive categories that group officers by similar specialties, occupations or ratings.

Current law grants the services broad authority to establish competitive categories for officer promotion. Navy has chosen to use 20 but the Marine Corps only group all officers into two. The committee favors Navy’s approach.

Another DOPMA reform provision would prohibit the practice of requiring service secretaries to provide consistent promotion timing or promotion opportunity across competitive categories of officers in each service.

Other DOPMA reforms in the bill wouldn’t be mandatory. The services could use them if they desire. But even a few of these “will be controversial,” said retired Army Col. Michael J. Barron, director of government relations for Military Officers Association of America. One such provision would expand use of “constructive credit” to infuse commissioned ranks with move civilian expertise, for example to strengthen cyber warfare capabilities or take account of private sector training. It would allow direct commission of civilians up to the rank of colonel or Navy captain.

“That’s one of the most controversial topics when I talk to folks about DOPMA on Capitol Hill and in the services. The issue is, ‘Why can’t we go get someone who’s worked for a Google or Facebook, had a successful career, and give them a lateral [entry] promotion” to field grade rank. It would be very targeted if they moved forward on it,” Barron predicted.

But it still would rub up against service culture, particularly for the Marine Corps or Army where, Barron said, by the time an officer is promoted to major “they are inculcated into service culture in every way, shape and form” versus being a civilian in Silicon Valley on Friday and a major on Monday, Barron said.

“Can it work? I think it can; we did it during World War II in different areas. Very selectively though. The services would probably say ‘We’ll want to control that’ and not be mandated on how many they must bring in by lateral entry.”

The House version of the defense authorization bill contains no provisions to reform DOPMA. If the Senate package survives floor debate later this summer and clears the full Senate, a House-Senate conference committee will negotiate differences in the separate defense bills. Barron said he would expect the services to urge House conferees to embrace only some “targeted” DOPMA reforms and reject provisions that threaten management practices they want preserved.

At the January hearing on DOPMA reform, Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), subcommittee chairman, said the law was passed in the Cold War to provide “a fully ready officer corps comprised of youthful, vigorous” and mostly males “to defeat the Soviet threat.” It “largely serves its intended purpose.” DOPMA strengthened an “up-or-out” promotion system. But its once-desired outcomes, Tillis said, have grown “increasingly irrelevant for some threats facing today’s military.”

He cited three weaknesses reflected in the full committee’s report on its bill. One, Tillis said, the system for managing officers “is unable to quickly provide the officers required to respond to unforeseen threats that demand unexpected skill sets.” Cyber and information warfare expertise are most often cited.

Two, the system doesn’t respond effectively to “rapid changes in the defense budget, resulting in inefficient and systemic surpluses or shortages” of officers.

Three, DOPMA is one-size-fits-all solution to officer management which does not allow the services “much ability to differentiate” recruiting and retention practices across service branches or to vary them enough by career fields.

DOPMA’s authors, Tillis added, “never envisioned the post-Cold War military,” which is 43 percent smaller than in 1980 and “constantly engaged” around the globe “in ways never predicted during the Cold War. Repeated overseas combat deployments strain the more traditional warfighting career fields while…new military domains” including cyber and space, “require entirely different officer skill sets.”

The committee said DOPMA’s up-or-out promotion system “remains an important foundation for officer personnel management. Not every officer can or should be retained for a full career.” But it needs more flexibility.

Here are other key reforms in the Senate bill:

End Predetermined Promotion Timelines –The committee says not every officer career field should “resemble a pyramid” with a large number of junior officers feeding fewer mid-level officers and fewer still senior officers. Some technical fields would be best served with relatively small numbers of junior officers supporting larger numbers of mid-level officers, the committee contends.

For these specialties, the bill would allow multiple promotion opportunities, abandoning concepts of in-zone, below-zone or above-zone promotion, and no longer excluding officers twice passed over for promotion to the same rank.

Having broader zones and using only an officer’s up-to-date record might allow promotion of the best qualified without regard to how long they have served.

This would be a radical new promotion method if a service wanted to use it. It also would address criticism that current selection boards are reluctant to pick highly qualified officers from below zone on concern that it means not selecting a fully qualified officer expecting a due-course promotion.

Promoting High-Performing Officers Ahead of Peers– The committee would authorize selection boards to place officers of particular merit higher on regular or reserve promotion lists, ahead of officers with more seniority based on date of rank. At the January hearing, the Marine Corps expressed the greatest satisfaction with current DOPMA practices. This was the single new authority it sought to reward top performers. The committee says the Coast Guard has used similar authority extensively “for the last 16 years with great success.”

Term-based Selective Continuation Process– As a practical matter the services allow officers in the rank of O-4 to continue to serve until 20 years and retirement eligibility. With the new, more portable Blended Retirement System, senators want the services to have a term-based selective continuation tool so that a twice passed O-4 with needed skills, for example, could be continued for two years or three years and then compete again for another term. This would encourage better job performance rather than allow such officers to mark time.

Expanded Spot Promotion Authority– Current law allows Navy to spot promote nuclear-qualified officers to positions requiring an O-4 (lieutenant commander) or an O-5 (commander) rank. The committee wants all the services to have spot promotion authority up to the rank O-6 to retain special skills as needed.

Expands to 40 Years Allowable Officer Careers– To retain needed technical expertise, the services would have authority extend careers of officers in O-2 and above to 40 years. Under current law, officers face mandatory retirement, for example, an O-5 at 26 years, an O-6 at 30 years, to sustain promotion opportunities for more junior officers. The services could selectively waive these mandates to keep particular skills or experience they need.

Repeal Age-based Officer Appointment Requirements– DOPMA prohibits recruitment of an officer who can’t complete at least 20 years by age 62. Service rules are even tougher, declining to recruit officers older than 36 or 37. The committee wants to end the statutory bar on commissioning persons older than 42 to give the services greater flexibility to bring in the expertise they need.

To comment, write Military Update, P.O. Box 231111, Centreville, VA, 20120 or email milupdate@aol.com or twitter: @Military_Update.

|

Tom Philpott has been breaking news for and about military people since 1977. After service in the Coast Guard, and 17 years as a reporter and senior editor with Army Times Publishing Company, Tom launched "Military Update," his syndicated weekly news column, in 1994. "Military Update" features timely news and analysis on issues affecting active duty members, reservists, retirees and their families. Tom's freelance articles have appeared in numerous magazines including The New Yorker, Reader's Digest and Washingtonian. |

|

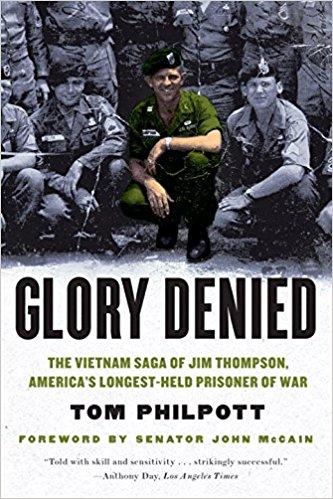

His critically-acclaimed book, Glory Denied, on the extraordinary ordeal and heroism of Col. Floyd "Jim" Thompson, the longest-held prisoner of war in American history, is available in hardcover and paperback on Amazon. |