The Civil War ripped apart nearly every bond Americans shared — classmates, friends, even family members found themselves on opposite sides of the conflict. One of the most unique feuds came in the winter of 1864, when a Union general defeated an entire Confederate army led by a man who once sat in his classroom at West Point.

At the Battle of Nashville, Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas, a Virginian who stayed with the Union, smashed the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood. Fifteen years earlier, Thomas taught artillery and cavalry tactics at the U.S. Military Academy. One of his cadets was the brash young John Hood. In December 1864, the teacher met the student again — this time across a battlefield — and the professor taught his last, and most decisive, lesson.

The Professor and the Pupil

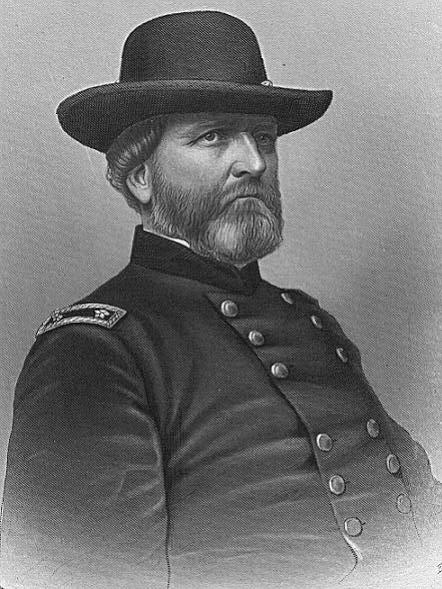

Thomas graduated from West Point in 1840 and fought with distinction and was wounded in Mexico. He returned to West Point in 1851 as an instructor, teaching artillery tactics and cavalry techniques to up-and-coming officers. His teaching style reflected his battlefield persona: careful, patient, deliberate.

Hood, who entered the academy in 1849, was the total opposite. He scraped by academically and graduated near the bottom of his class, but he radiated confidence and determination. Where Thomas valued steadiness, Hood leaned into aggression.

When the Civil War erupted, their choices reflected their temperaments. Thomas stayed loyal to the Union, even though his family in Virginia disowned him for it. Hood threw in with the Confederacy, rising quickly through the ranks on sheer aggressiveness. By 1864, Thomas commanded the Union’s Army of the Cumberland; Hood, despite losing movement in his arm at Gettysburg and a leg at Chickamauga, commanded the Confederate Army of Tennessee.

Clash at Nashville

In the fall of 1864, Hood led his battered army north to draw Union forces away from Sherman’s march to the sea in Georgia. It was a desperate move. At Franklin in November, he hurled his men against fortified Union lines in one of the war’s bloodiest frontal assaults. More than 6,000 Confederates fell, including much of Hood’s officer corps.

Despite the horrendous losses, Hood kept pressing north. Outside Nashville, he dug in with about 30,000 men. Thomas waited inside the city with nearly 55,000. He refused to attack during a crippling ice storm, despite constant pressure from Ulysses S. Grant. Despite his stellar record in previous battles, Thomas’ constant reluctance to attack nearly made Grant fire him; he even began referring to Thomas as “old slow trot.”

On December 14, Thomas finally wired Washington: “The ice having melted away today, the enemy will be attacked tomorrow morning.”

At dawn on December 15, Thomas put his plan into motion. On his right, Maj. Gen. James Steedman launched a diversionary attack, his division including regiments of Black Union soldiers. They fought uphill against entrenched Confederates, taking heavy losses but holding enemy attention.

On the Union left, Thomas delivered the real blow. Gen. James Wilson’s cavalry and IV Corps under Thomas Wood swung wide, overrunning a chain of Confederate redoubts and artillery. By nightfall, Hood’s flank had collapsed, and his army fell back over two miles. That night Thomas telegraphed Grant: “I attacked the enemy’s left this morning and drove it from the river … I shall attack again tomorrow.”

The next day, Thomas pressed the attack. Union troops converged on strongpoints at Overton Hill and Shy’s Hill. At Overton Hill, repeated charges — including those by the U.S. Colored Troops — were repulsed with bloody losses. But at Shy’s Hill, the Union breakthrough came. Wilson’s cavalry and Wood’s infantry stormed the position, sending Hood’s left wing reeling. Confederate lines collapsed into a full retreat.

By nightfall, the Army of Tennessee was finished. Thousands of Confederates fled south in chaos, many throwing down their rifles as they ran.

The Aftermath

In two days, Hood lost another 6,000 men — on top of the Franklin disaster. Union casualties were about half that. His army retreated to Alabama and never fought as a serious field force again. Hood resigned in January 1865.

For Thomas, Nashville was the crowning achievement of a career built on his steadiness. Already nicknamed the “Rock of Chickamauga” for saving Union forces in 1863, he had now delivered one of the most crushing victories of the war. Grant, who had nearly relieved him, admitted afterward that Thomas’s patience and preparation had been vindicated. Although he never gained the recognition of other Union commanders, Thomas was instrumental in the defeat of the Confederacy.

Thomas would later speak of his former student: “Hood is a good fighter, very industrious on the battlefield, careless off, and I have had no opportunity of judging his action, when the whole responsibility rested upon him. I have a very high opinion of his gallantry, earnestness, and zeal.”

For Hood, Nashville became the symbol of reckless leadership. In his memoir Advance and Retreat, he defended his decisions, but history remembers him as the student who was bested by his own aggressiveness — and by the professor who had once taught him the science of war.

The Civil War was full of personal tragedies, but few matched the irony of the Thomas and Hood battle: a Virginian loyal to the Union destroyed the army of his own former student. On the icy hills outside Nashville, George Thomas proved that in war, patience and discipline could crush even the boldest attacks.