On the morning of Oct. 23, 1983, a suicide bomber crashed a truck loaded with 2,000 pounds of explosives into U.S. Marine barracks at the Beirut International Airport in Lebanon. After the devastating blast, little was left of the four-story building that housed hundreds of United States service members. Among the fallen were 220 Marines, 18 sailors and three soldiers.

The Marines had not seen a deadlier attack since Iwo Jima. The United States would not see a deadlier attack until 9/11.

Mark McNeill, now an execution manager for Naval Information Warfare Center (NIWC) Atlantic’s installation planning and execution department, was there.

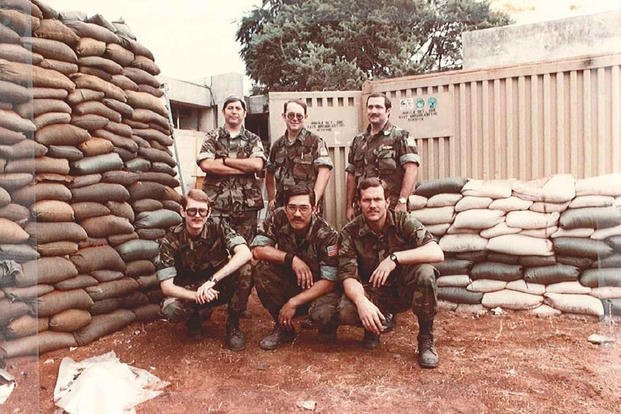

Then an interior communications electrician first class, McNeill was a lead broadcast engineer for the Navy broadcasting division of the U.S. Navy Office of Information (CHINFO). This select group took the unclassified mission mobile, going into the theater around the world as part of Navy broadcasting mobile detachments.

Deployed for peacekeeping, they also built television and radio stations across the globe.

“We established outlets, TV and radio stations around the world -- like ‘Good Morning, Vietnam,’ which is not far from context,” McNeill said.

According to McNeill, the team’s official unclassified mission was to entertain, inform and train. The Office of Naval Intelligence and other agencies provided content as part of the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service mission. The content included popular television shows such as “Happy Days” and “M*A*S*H,” along with Top 40 music and news wire feeds. All of the information was pre-recorded and arrived a week late, but as McNeill noted, this was pre-internet.

During radio broadcasts, which occurred at 7 a.m., noon and 5 p.m., everything would stop, and everyone would gather to listen.

“Part of the mission was to comfort forward deployed Marines and sailors, to give them that piece of home,” said McNeill.

The Navy broadcasting team also spent time getting to know the Marines and would give them shout-outs and updates on their favorite baseball teams on the radio, to help lift spirits in the frightening, often deadly, environment.

The night of Oct. 22, McNeill and two journalist colleagues were sheltering in a nearby bombed-out, brick-and-mortar building. Concerned for their safety due to a recent uptick in fighting, they set to work fortifying the shelter with plywood and sandbags.

“We thought we were about to get run over any day,” McNeill said. “We were very uneasy; we were always looking around. We were talking to the Marines all the time, [asking], ‘Hey, what’s going on over there?’ Every noise we heard -- car going down the street backfiring -- we all went on alert.”

They ran out of sandbags with about a foot or two to go, McNeill recalled. Exhausted, the men arranged some boxes between their cots and the window as an added precaution, left their boots open and guns at the ready, and fell asleep.

The bombing occurred at 6:22 the next morning.

One of McNeill’s colleagues had already left the shelter to play the daily 6 a.m. recording of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” He had been protected from the blast as he shaved in a nearby restroom and came running to find his roommates.

The men put on their boots and flak jackets and grabbed their guns. Outside was a chaos of noise and destruction. Their former bunker, a five- or six-story building, was lying on top of their former camp, and a large portion of it was on top of the building they had slept in, according to McNeill.

McNeill immediately went into rescue mode. “We were very well-trained,” he said of his team. “We could be deployed within 24 hours around the world. We were running these TV and radio stations, but we also had to support the military missions for whatever reasons we were there.”

He and a colleague pulled more than 20 people from the rubble.

“It was horrible. I still have nightmares about the sounds and the smells … It was definitely something you wouldn’t want anyone to experience,” McNeill said.

They continued their rescue efforts until a senior chief, followed by the commanding officer, ordered them to put the radio station back on the air. McNeill spent a couple of hours repairing equipment damaged by the blast and restoring the radio station to working order.

As the music of the AM radio rolled from the speakers, the overall feeling of the war-torn area began to shift. “It had a calming effect, and that’s what we were there to do,” McNeill said.

Though McNeill sustained wounds, he was not evacuated after the bombing. The Navy broadcasting team stayed in Lebanon and carried out their mission, helping in any way that they could, until they returned stateside around Thanksgiving.

“We just went and did what we were expected to do. We didn’t do anything special; in our eyes, we were doing what we were trained to do,” he said.

McNeill, who joined the Navy in 1976, retired after 22 years of service. He worked for General Dynamics before coming onboard at NIWC Atlantic in 2012.

In 2018, McNeill was honored during a reception at the White House commemorating the 35th anniversary of the attack on the Beirut barracks. The event was attended by President Donald J. Trump and then-Defense Secretary James Mattis.

During the ceremony, Trump expressed how thankful he was to have the veterans of the Beirut attacks present. “This is an incredible group,” Trump said to the veterans, whom he had invited to stand. "You courageously survived that terrible October day, and you have made your ‘first duty to remember.’”

Toward the end of his remarks, Trump said, “In all of our history, no figure has ever lived with more grace and courage than the men and women who serve our country in uniform.”

Today, McNeill continues to serve the warfighter through his work with NIWC Atlantic’s installation planning and execution department, which is responsible for afloat and shore modernization planning for the Atlantic fleet.

In his position as execution manager, McNeill oversees the modernization of aircraft carriers. Currently, his team is updating shipboard networks with Consolidated Afloat Network and Enterprise Services, adding a variety of updated applications for ship maintenance, replacing antennae and running cables throughout the USS George H.W. Bush (CVN 77).

“Working as an on-site installation manager affords me the daily satisfaction of knowing how honorable it is to continue my civic duties in support of our nation’s defense,” McNeill said.

As a part of Naval Information Warfare Systems Command, NIWC Atlantic provides systems engineering and acquisition to deliver information warfare capabilities to the naval, joint and national warfighter through the acquisition, development, integration, production, test, deployment and sustainment of interoperable command, control, communications, computer, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, cyber and information technology capabilities.

Stay on Top of Your Veteran Benefits

Military benefits are always changing. Keep up with everything from pay to health care by signing up for a free Military.com membership, which will send all the latest benefits straight to your inbox while giving you access to up-to-date pay charts and more.