It's rare for a sitting U.S. president to issue any kind of apology, but on Oct. 3, 1995, Bill Clinton issued one to veterans and civilians involved in government-administered, human radiation experiments between 1944 and 1974. It was the final outcome to a report he had commissioned the previous year, allowing veterans who had previously been sworn to secrecy to speak up about their experiences as the government declassified hundreds of thousands of documents related to the tests.

Clinton's apology was a major moment for many "atomic veterans" who had been effectively forbidden from even seeking medical treatment, let alone discussing their experiences with each other, for decades. Unfortunately, very few of those veterans ever saw it or realized they were no longer bound by their oath of silence. That same day, American news media was busy covering a different, more sensational story: the O.J. Simpson trial verdict.

In January 1994, Clinton had created the Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments (ACHRE) through an executive order that opened thousands of documents and freed atomic veterans to talk openly about the experiments the U.S. government subjected them to as far back as 1944, regardless of their location or classification. The committee gathered the documentary evidence and held 31 days of public hearings. The results were damning.

"We found that government officials and physicians who had the trust of the public and of their patients abused that trust," committee chair Ruth Faden said during Clinton's press conference. "Patients were used as subjects of experiments without their knowledge or consent. Information was withheld from affected communities and from the public. Secrets were kept to protect the government from embarrassment and legal liability."

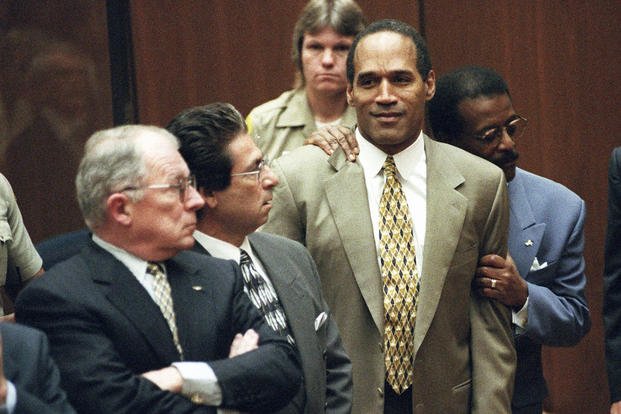

That apology was completely eclipsed by developments in criminal case against O.J. Simpson, who died from prostate cancer on April 10, 2024. After being charged with the murder of his wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman, in June 1994, the former football star turned actor left a suicide note, disappeared and then reemerged to lead the Los Angeles Police Department on a high-speed chase in his now-infamous white Ford Bronco. Some 90 million people watched the Super Bowl that year, but an estimated 95 million people watched the O.J. Simpson drama. The chase ended peacefully and Simpson was apprehended, but the trial of the century was about to begin.

From the day of Simpson's arraignment on June 20, 1994, until the day the verdict was delivered on Oct. 3, 1995, updates on the Simpson trial dominated print and broadcast media. It wasn't only news coverage superseded by the courtroom drama; much to the chagrin of soap-opera fans, television networks repeatedly interrupted their favorite daytime TV series in favor of the new reality show unfolding live in a Los Angeles courtroom. Simpson's trial reflected more than his perceived guilt or innocence. Coming on the heels of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, it was a flashpoint for race relations in the country while highlighting what "justice" meant for celebrities versus the everyday American.

By the time the jury reached a verdict, the media frenzy had reached a fever pitch, with networks breaking into their regular coverage for live results from the courtroom. An estimated 150 million Americans watched the verdict live, and the proceedings left little room for anything else -- including Clinton's apology. "ABC World News Tonight" dedicated half its broadcast to the Simpson verdict that night, but gave a mere three minutes to the atomic veterans story. PBS's "MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour" led with a lengthy package on the verdict before moving on to a shorter one on Clinton's press conference.

"The President's apologizing for the wrongdoing was very significant. Presidential or national apologies are actually relatively few and far between," Faden, the committee chair, recalled in a 2016 documentary on atomic veterans. "But it is true the report's release was completely trampled by the O.J. verdict coming out."

It's hard to overstate how significant the ACHRE report was. It revealed that over a 30-year period starting in 1944, some 4,000 experiments were conducted on U.S. troops, prisoners, terminally ill patients, children and civilians to test the effects of radiation and nuclear weapons on the human body. It began in an effort to understand the risks taken by those working to build the first atomic bomb, where Manhattan Project test subjects were injected with polonium, plutonium and uranium.

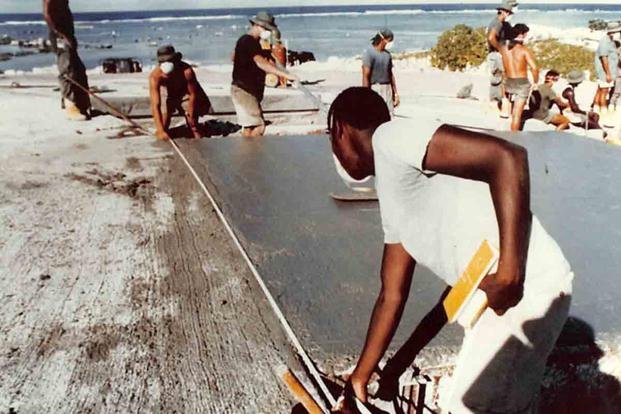

Later, experiments used children, who were exposed to radioactive iron and calcium without their parents' knowledge. The U.S. government also repeatedly released radiation into the environment to research fallout patterns. Some 400,000 soldiers and sailors were exposed to 1,000 nuclear blasts in the South Pacific, with some as close as one mile to ground zero. They had only jackets, helmets and gas masks for protection, if they had anything at all. Those troops were sworn to secrecy, facing a punishment of 10 years in prison and a $100,000 fine for revealing their roles in the tests.

But secrets involving hundreds of thousands of people don't stay secret for very long. In 1986, the House of Representatives released a report on the subject, "American Nuclear Guinea Pigs: Three Decades of Radiation Experiments on U.S. Citizens." That report admitted the government covered up the unethical nature of the experiments and misled families of the victims who later died. Clinton's executive order creating ACHRE was itself a response to reporter Eileen Welsome of The Albuquerque, N.M., Tribune who, in a six-year investigation published in1993, uncovered evidence of 18 people injected with plutonium without their informed consent.

Testing had ended in 1974, when the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare adopted regulations governing the use of human test subjects. ACHRE released its findings, and President Clinton gave his apology in the same Oct. 3, 1995, press conference that the report came with the promise of remuneration for those affected by the testing.

In many cases, that remuneration was desperately needed. Veterans and their families had long experienced what they believed were the effects of radiation. Boils breaking out all over their bodies, lost teeth, rare cancers and genetic defects were reported among the veterans, but the VA insisted the death rate among "atomic veterans" was not higher than the general population. It's a stance the veterans never believed, and they kept fighting to get compensation and medical benefits. Meanwhile, studies based on individual tests reveal heightened links to radiation-related deaths.

After the release of the American Nuclear Guinea Pigs report, Congress passed the Radiation-Exposed Veterans Compensation Act of 1988, which extended VA benefits to those affected by certain cancers or those who served in the U.S. occupation of Japan after World War II. It did not extend to everyone involved in the human radiation experiments.

Despite all the experimentation, the U.S. military didn't actually collect much data on how much radiation to which the soldiers and sailors were exposed. It was primarily concerned with where gamma radiation was distributed after a nuclear blast and if U.S. troops could continue moving in the wake of such an explosion.

Without radiation dosage information, linking certain cancers to radiological exposure is difficult for researchers. The VA and Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) make speculative estimates when considering a veteran's service connection for these cancers, speculations the National Academy of Sciences criticized as "underestimated, sometimes considerably" with "little evidence of quality control" in a report published in 2003.

That report also found most veterans were not contacted to discuss their exposure scenarios, and because the O.J. verdict overshadowed the Clinton apology, many of them likely had no idea they were even allowed to talk about what happened to them, even after the president declassified their experiences. Over the course of decades following the atomic testing, information that might have linked their radiation exposure to their conditions were not a part of the veterans' medical histories, simply because they weren't allowed to tell anyone -- even their doctors.

"Most of the atomic veterans didn't even know the oath of secrecy was lifted," Morgan Knibbe, who produced a 2019 documentary "The Atomic Soldiers," told The Atlantic at the time. "Most went on to believe that they were not allowed to talk about their experiences, even to seek help for their health problems. Many took the secret to their grave."

It would be near-conspiratorial to suggest that the Clinton administration planned its public apology for the day of the verdict, when it knew nobody would be paying attention. More likely than not, the verdict's impact on atomic veterans was a historical coincidence, one that reflects the media's increasingly frenetic attention span in an increasingly connected world.

And even with recent recognition, atomic veterans still have a way to go to receiving the recognition (and remuneration) they deserve. The PACT Act is the U.S. government's latest legislation aimed to address the health problems of veterans exposed to toxic substances during their service. The legislation is supposed to include atomic veterans, but requires the veteran to prove they were not only there, but also provide proof of their radiation dosage from a DTRA estimate, as well as proof that dosage caused their presumptive condition.

As of 2024, the VA has rejected 86% of those claims.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.