The U.S. Navy will name its newest Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer for World War II hero Charles Jackson French, who saved 15 of his fellow sailors from certain death by exposure or execution. In a daring feat of strength and endurance following an enemy attack that sank the USS Gregory on Sept. 5, 1942, French swam his shipmates out of danger by towing their life raft with a line tied around his waist. The feat earned him the nickname "The Human Tugboat" and "Hero of the Solomons."

And very nearly nothing else. It would take one of the shipmates he rescued, an ensign who refused to forget the courage and unyielding determination French displayed that day, for the young Black sailor to get even a modicum of the recognition he deserved.

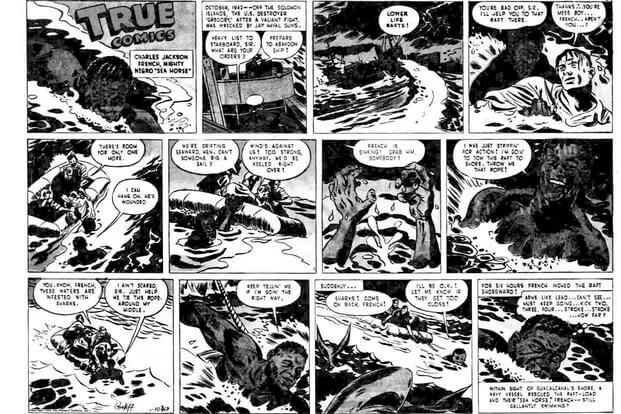

On Oct. 21, 1942, Ensign Robert Adrian appeared on an episode of the weekly NBC radio show, "It Happened in the Service." Adrian was an officer on the destroyer USS Gregory and was on the bridge when it was attacked by the Japanese. He told the audience the story of Charles Jackson French.

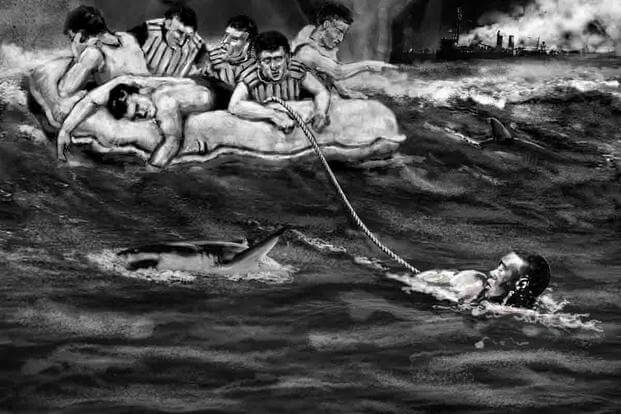

Adrian was knocked unconscious in the attack, but was somehow taken off the bridge and helped into the water before the ship sank. Wounded, he could hear the Japanese shooting into the survivors' bodies. In the darkness, he found a life boat filled with wounded sailors. The only uninjured crew member was a Black mess attendant known only as "French." When Adrian told French that the current was taking them toward a nearby island, and that they would be captured by the Japanese garrison there, French took off his clothes and told his officer he was more afraid of the Japanese than of the sharks.

"Just keep telling me if I'm goin' the right way," he reportedly said.

For the next eight hours, French towed the raft away from the unfriendly shores and out into the waters of the Pacific Ocean. He swam through the night until a friendly scout aircraft spotted them the next day and sent a Marine landing craft to recover them. The next day, the story was picked up by The Associated Press, which led to his appearance on a War Gum Trading Card Company card. It wasn't long before "French" was revealed to be a 22-year-old sailor named Charles Jackson French.

French was born in 1919 and raised in Foreman, Arkansas, where many believe he learned to swim in the wild waters of the Red River, just more than 10 miles away from where he grew up. Sadly, he would be orphaned as a teen and sent to live with family in Omaha, Nebraska. When he turned 18 in 1937, he joined the Navy as a mess attendant, one of the few jobs available to Black sailors at the time. He was sent to the Hawaii-based cruiser USS Houston, the one-time flagship of the Asiatic Fleet, and even hosted President Franklin D. Roosevelt during his enlistment.

In 1941, French's time in the Navy was over, so he took his discharge and went back home to Omaha. Not long after he settled into civilian life, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor. Four days after that day of infamy, he reenlisted in the Navy once again with the rating of mess attendant. This time, he was stationed aboard the Gregory, a World War I-era destroyer modified to fit modern arms and move troops.

French and the Gregory were en route to the Pacific in March 1942 when his old ship, the Houston, was sunk by the Japanese at the Battle of Sunda Strait. Only 368 of his former shipmates survived the sinking and were all taken captive by the Japanese, but no one knew that until they were liberated after the war. By July of that year, the Gregory and its task force were headed for Guadalcanal, landing their troops on Aug. 7. From there, their mission was to patrol the waters, bring up supplies and ferry troops.

On the night of Sept. 4, the Gregory was returning to Tulagi with another destroyer, the USS Little, when both were caught in the open by three enemy destroyers and a cruiser. At first, their position was hidden by the deep black of the ocean night. The Japanese firing on Guadalcanal's Henderson Field had alerted the Americans to their presence. A Navy pilot, assuming the fire had come from a Japanese submarine, dropped a series of flares on the Americans, lighting up their position in the night.

They were immediately outgunned. Three minutes later, the Japanese had opened fire on the Gregory, and the ship was beginning to sink. With the vessel burning, its wounded captain ordered the crew to abandon ship. Some 20 minutes after that, the Japanese began firing again, this time aiming for the crewmen in the water.

For those who survived, the choices were bleak. It would take all night to try to swim to Guadalcanal, and they would have to do it in shark-infested waters. If they floated to shore, they'd be taken prisoner, and being captured by the Japanese meant harsh imprisonment or execution. But some of them were saved because one enlisted sailor stood up and tied a rope to himself and the raft, then jumped into the water.

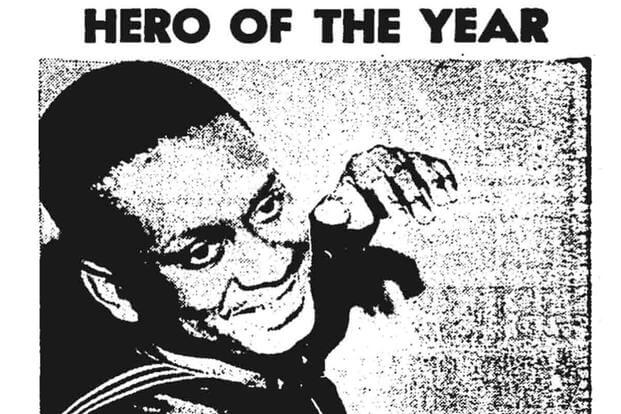

Ens. Adrian never learned French's full name, because he'd been wounded and hospitalized. The Pittsburgh Courier newspaper reported that French had not only pulled the life raft, but had initially found it empty and pulled as many crewmen as possible aboard it. French himself would return to Omaha to cheering crowds (of all races), would appear at bond drives and in comic strips. Adrian also learned his account of the incident led to French being recommended for the Navy Cross.

When time for his recognition came, all French received was a letter of commendation from Adm. William "Bull" Halsey. It turned out Cmdr. H. F. Bauer, the skipper of the Gregory, had received the Silver Star for his heroism that morning, and all-powerful Navy tradition dictated that a subordinate would be unlikely to see a higher award than his CO. French was discharged from the Navy on March 9, 1945. He died on Nov. 7, 1956, of conditions related to alcoholism.

It was the International Swimming Hall of Fame and its exhibit on Black Swimming History that kept French's story alive. It sparked interest in a retired Navy veteran who happened to see it and connected French’s story to the family of Robert Adrian. Adrian had survived the war and went on to a long career in the U.S. Navy, retiring as a captain in 1966. He died in 2011, but his family had more to say about French.

It turns out that Adrian would never talk about his wartime service, except when it came to talking about French. He even kept a recording of his episode of "It Happened in the Service." Adrian had tried to find French after the war, but never could. He even wrote his story in "Tin Can Alley," a newsletter for destroyer veterans. Called "Our Night of Hell off Guadalcanal," it told French's story and about Adrian's push to award French the Navy Cross.

The International Swimming Hall of Fame also published a Memorial Day post on its website about French, which went viral and moved the Navy's public affairs officer and chief of information to "look into whether we can do more to recognize Petty Officer French." Some called for him to finally receive the Navy Cross while others pushed for the Medal of Honor.

The result was the surface rescue swimmer training pool located at Naval Base San Diego being named in his honor, as well as an Omaha post office. He also received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, a non-combat award for heroism at life-threatening risk. The naming of the latest Arleigh Burke-class destroyer is the latest in an effort to recognize what French did that day properly.

During World War II, 432 service members received the Medal of Honor for actions taken during the war. No Black men received the award for World War II until 1997, after the Army made a systematic review of its records and discovered the widespread racism involved in the process of awarding the Medal of Honor. Only one of the recipients was still alive when President Bill Clinton finally presented seven of the awards.

In 2021, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin ordered a systematic review for all records of Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross and Air Force Cross Medals awarded to Black and Native recipients from all wars. He noted the Army and Navy had already done that for World War II, but the Navy apparently found no instances of Black sailors who deserved an upgrade. The story of Charles Jackson French might suggest the scope of that review was too limited.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.