For 60 years, a World War II-era B-17 Flying Fortress sat atop an Oregon service station, serving as a canopy for customers stopping to refuel. It only made it there after an incredible cross country journey that involved smuggling booze and a two-plane pileup on an Oklahoma runway.

Art Lacey created the "Gas Station Bomber" -- one of Milwaukie, Oregon's most visited sites -- on a five-dollar bet.

According to his daughter Punky Scott, the now-deceased Lacey was attending a birthday party in 1947 when he told fellow revelers he was going to put a B-17 bomber on top of his local gas station. He'd learned about the surplus of B-17s and that they could be acquired for near-scrap value. He wanted to use the warplane's wings as a canopy for his gasoline pumps.

One of the partygoers told him he was crazy and it would never happen. Lacey bet the man $5 that it would. While at the same party, Lacey asked a friend for a $15,000 loan. That friend was allegedly involved with some less than legal businesses.

"And the guy had it on him," Scott said in an interview with ABC affiliate KATU. "I don't know how that translates into today's money, but it's got to be a lot."

It is a lot, roughly $200,000 when adjusted for inflation. But Lacey didn't bat an eye at the number; he had his eyes on the prize. He took the money and drove to Altus Air Force Base in Oklahoma, which was then a scrapyard for World War II aircraft.

There, Lacey used his skills as a salesman to negotiate the purchase of a used B-17. The commander of the base agreed to the purchase for $13,000 and told Lacey he'd have the plane fueled and ready the next day. All Lacey had to do was show up with a co-pilot. Now he had more problems.

He had neither a co-pilot nor the experience needed to fly a Flying Fortress. Despite the dire nature of both these issues, neither prevented Lacey from showing up the next day. He was going for the gusto and would not be deterred.

"He knew how to fly a single-engine aircraft and was a good pilot," Scott said, "But he didn't know how to do the big ones."

Lacey arrived at Altus with a mannequin he'd borrowed from a local seamstress, dressed it up and then began to read the manual as he practiced the controls on the runway. He might have gotten away with it, had it not been for a landing gear malfunction that caused him to crash into another B-17.

Uninjured, save for his pride, he was forced to admit to the Air Force that he couldn't fly a B-17. Luckily, the bill of sale hadn't been written up yet. The commander "took pity" on Lacey and told him he would chalk it up to "the worst case of wind damage I've ever seen," before selling him a second airplane.

This second plane had only 50 hours of flight time on it and was in much better condition, which included its landing gear. Altus' commander even sold him the new plane for $1,500 (just over $20,000 in today's dollars). To get the plane home, he called his wife to send over two friends, a pilot instructor and an Army Air Forces veteran who was a B-17 crew chief during the war. He also needed a case of whiskey.

With zero money left, Lacey needed money for fuel. The whiskey was meant to bribe the local fire department to siphon gas from the two crashed B-17s into his plane. Since alcohol sales were illegal in Oklahoma at the time, the whiskey had to come from somewhere else.

The next morning, Lacey's B-17 and its crew were in the air, headed for Palm Springs, California, to refuel. Since Lacey still had no money, he bought the fuel using a bad check (he would cover the debt when he returned to Oregon). When they finally landed in Troutdale, Oregon, they disassembled the old plane and loaded it onto trucks.

But when Lacey and his crew went to get the required permits to make the 45-minute drive to Milwaukie, they were denied. The trucks were too high, too long, and "everything was wrong," according to his daughter's recollection.

"So he hired a motorcycle escort for funerals," she said. "And the guys are in black leather and they put him out in front in the middle of the night and had two teenagers ride along with him. And he told them, 'Now if the police show up, you burn rubber in another direction and they'll follow you.' And he told the trucking drivers, 'You just keep going. I'll pay any tickets, just keep on going and don't let them stop you.' "

When the officials found out he'd done it anyway, they came after him for skirting the permits. The local newspaper came to the rescue, drawing on Oregon's postwar patriotism to fuel public sentiment in support of giving the B-17 Bomber its "final resting place" in Milwaukie. He ended up with a $10 fine, which he paid.

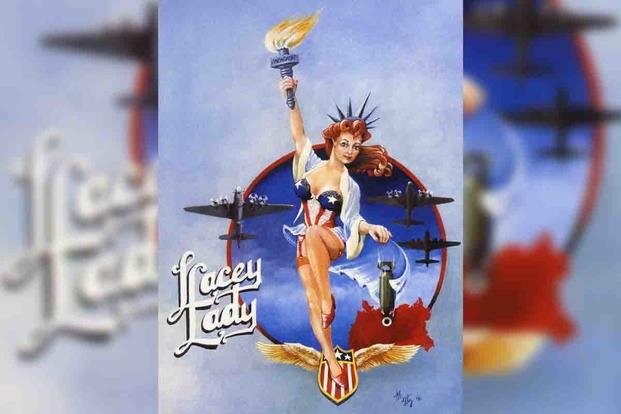

Art Lacey died in 2000, but the aircraft, nicknamed "The Lacey Lady," called Milwaukie home for more than 60 years. As of 2021, it was in pieces in an aircraft hangar and is being restored by the B-17 Alliance Foundation to be turned into a flying museum.

You can help the restoration of "The Lacey Lady" and other World War II B-17 Flying Fortresses by donating on the B-17 Alliance Donation Page.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.