Welcome to the first episode of Military.com's new podcast, Left of Boom, hosted by Hope Hodge Seck, managing editor for news. Every day, our reporting team is out there covering the news affecting the military community. But we felt we wanted a place to go deeper on the topics you care about, and to let you hear directly from the legends and trailblazers and changemakers who have left their mark on the military. So that's what we'll do.

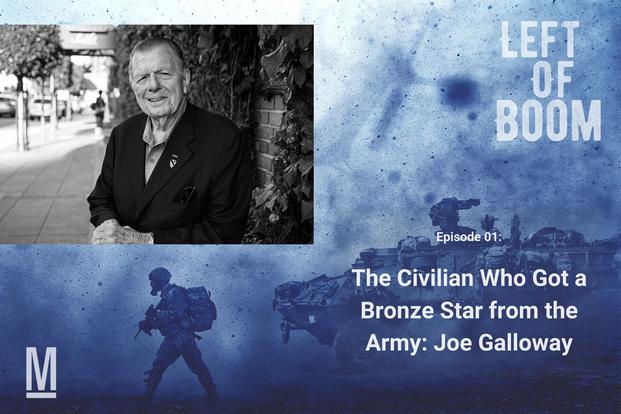

In this, our first episode, we'll talk to Joe Galloway, a war correspondent whose coverage of the Vietnam War helped shape how we remember and understand it. His book about the Battle of Ia Drang inspired the 2002 blockbuster We Were Soldiers, and he has been portrayed in film by no fewer than three A-list actors. Much more impressively, he's the only civilian to ever receive the Bronze Star for combat valor for heroism in Vietnam from the Army. Now he has a really special new book out, They Were Soldiers, about the incredible lives of various people who served in Vietnam.

Subscribe to the Left of Boom podcast:

iTunes | Google Podcasts | Spotify | TuneIn | Stitcher

Mentioned in this episode:- The Battle of Ia Drang

- They Were Soldiers

- The Army

- The Vietnam War

- Lt. Gen. Hal Moore

- The Bronze Star

The following is an edited transcript of this episode of Left of Boom:

Hope Hodge Seck 0:00

Welcome to the first episode of Military.com's new podcast, Left of Boom. I'm Hope Hodge Seck, managing editor for news. Every day, our reporting team is out there covering the news affecting the military community. But we felt we wanted a place to go deeper on the topics you care about, and to let you hear directly from the legends and trailblazers and changemakers who have left their mark on the military. So that's what we'll do. In this our first episode we'll talk to Joe Galloway, a war correspondent whose coverage of the Vietnam War helped shape how we remember and understand it. His book about the Battle of Ia Drang inspired the 2002 blockbuster We Were Soldiers, and he has been portrayed in film by no fewer than three A-list actors. Much more impressively, he's the only civilian to ever receive the Bronze Star for combat valor for heroism in Vietnam from the Army. Now he has a really special new book out, They Were Soldiers, about the incredible lives of various people who served in Vietnam. Joe Galloway, It's an absolute honor to have you on the show.

Joe Galloway 1:02

Good to be with you, Hope.

Hope Hodge Seck 1:03

First of all, I hope you're staying well and safe. How are you spending your quarantine time these days?

Joe Galloway 1:09

Well, when I'm not doing Zoom, interviews and lectures, I've got a pile of books unread and I'm working my way through them.

Hope Hodge Seck 1:22

What are you reading right now?

Joe Galloway 1:23

I just finished reading one called Where the Crawdads Sing or something like that -- a novel about growing up and murder and all sorts of swamp things.

Hope Hodge Seck 1:38

Do you find you read more fiction than nonfiction in your spare time? Or is it a mix?

Joe Galloway 1:43

It's a mix. It's a mix. I try to keep my eye on what's what's good and military history, but I read a lot of fiction too.

Hope Hodge Seck 1:57

That's fantastic. So, as a journalist who has covered the military and spent a little time downrange, I counted a special treat to speak with you. I'd put you and probably Ernie Pyle on my short list of people whose feet I'd just like to sit at and sort of absorb everything that you know.

Joe Galloway 2:15

You're gonna make me blush.

Hope Hodge Seck 2:20

So selfishly, I have to ask, what do you think of the field of military reporting and war correspondents today? What is changed? What has stayed the same? And overall, how do you think we're doing at telling these important stories of conflict?

Joe Galloway 2:36

You know, the technology has advanced so far since Vietnam. I had to survive the battle and get out and ship my film to Saigon, get somebody to carry it for me on a military flight. I had to get on the military phone system, which was very creaky and went through about 12 different switch boards between the islands and Saigon. And there were priority 1, 2, 3 and 4, and reporters were at the bottom of 4, which meant any Spc-4 could knock you off -- until we learned to say, 'this is Col. Smith, Priority 2. But it would still take maybe four or five hours to dictate 400 words to my office in Saigon. You know, and you you saw technology in the Gulf War. I think Dan Rather had a 18-wheeler flatbed with 18 tons of equipment in Kuwait City so he could do an uplink, and the next time we went out everybody had a pocket satellite phone or two we said that at Knight Ridder we sent everybody into the field with two different sat phones on two different systems in case one went down, and one did go down during the war. So it was a good move. You know, I think about what it would have been like for Hal Moore in the Ia Drang battle. If I'd been sitting there on a sat phone and his bosses had been reading my stuff, probably, he would have stomped on my sat phone. He didn't need anybody looking over his shoulder, real time. And sometimes I wonder how much good our technology is doing for the military and for ourselves. I often thought that if I am good enough and the Buddhists are right, and I get to come back, I'd like to come back as the Times of London correspondent in Singapore in about 1856. And it would take three or four months for the P&O steamer to bring a letter from my boss in London, and three or four months for the steamer to take my response back to him. And I think that's about the right amount of time you need to correspond with your call.

Hope Hodge Seck 5:29

I like that. I'll ask just one follow up, which is when we kind of set aside the technology and talk about that important balance between accountability, holding the military accountable and telling the stories of the servicemen and women fighting downrange. How has that changed? And do you think that presents a different challenge today than it did in the Vietnam era?

Joe Galloway 5:56

I'm not sure. I think we've always tried to hold their feet to the fire when necessary. Back then, today, tomorrow. That's our job. The way the news is handled, the way news people are handled, varies from administration to administration. I think right now we're in a particularly challenged environment, when the commander in chief looks upon the media as the enemy. And I thought that the, the USS Theodore Roosevelt incident was very telling, in terms of the attitude of the higher-ups toward the truth and the news and how they handle their own captains. So, you know, I think it's a mixed bag. We've still got the same job to do, we have to do it to the best of our ability in pursuit of the truth. You know, more than 70 of my good friends died in Vietnam pursuing the truth. It has to be worth something very real and very costly to be willing to put your life on the line to find it, and expose it and write it and tell the American people what's really going on on the battlefield. What's going on on on aircraft carrier, what's going on around the world.

Hope Hodge Seck 7:43

That's profound, thank you. To change the subject slightly, I understand in addition to your other many accomplishments, you've been the special consultant for the Vietnam War 50th anniversary commemoration project from the Pentagon since 2013. Is that role ongoing? And what does that entail for you?

Joe Galloway 8:04

Well, it's been for me the same thing from the beginning to right now and continuing for this year, I think will will shut down my part of it at the end of this year. But what my assignment has been is to travel all over the United States, doing video interviews with Vietnam veterans, all ranks all branches, civilians, Army nurses, military nurses, and doctors, everybody. And these usually run between an hour and a half, two hours each. And unedited copy goes straight to the Library of Congress, Oral History archives. And I would tell you that I don't make a lot of money doing this and I really hate airports and airplanes and I'm on them all the time. But I think it's important I think it's important that we capture as many of these stories before they're all gone. My this generation of veterans is dying off faster than the World War II people did. It is, it is, and there are reasons for that, not the least of them Agent Orange and the fact that a lot of them came home and self-medicated. You know, 3.3 million Americans were in Vietnam and are in the Indo-China theater during the war. Obviously, not all of them carried a rifle and fought in the jungle, but they were 3.3 million, and I think we're down to about a million now. I just think it's important that 100 years from now, a researcher can walk into the Library of Congress and sit down, do original research on the Forgotten War and the voices of the men and women who were up to their eyeballs in that war?.Who knows, maybe some of the best books are still far out on the horizon. I get to have a little piece of that.

Hope Hodge Seck 10:19

As you're speaking, there's a little twinge of longing for what might have been, thinking about the the World War I veterans and even the World War II veterans who are now in their 90s and wishing that a project like the one that you've embarked on, could have been done for prior generations with the same degree of thoroughness.

Joe Galloway 10:42

I think they made a good faith attempt with some of the surviving World War II vets, but I don't know how far it went. taken me. This is, I guess, the seventh year, and we have about 800 interviews in the can and we had hoped, before this virus shut down all DoD official travel, we had hoped to get that up to about 1000 this year. And I don't think we're going to get anywhere near that. We'll see.

Hope Hodge Seck 11:20

Is this in fact, this project, how your book, they were soldiers came about? Did these stories come from these interviews that you're doing now?

Joe Galloway 11:30

Not at all, in fact.I would have been poaching beyond permission to do that. So my co-author who is a fella named Marvin J. Wolf, who I first met in Vietnam 55 years ago when he was a spec for photographer with the first Cavalry Division public affairs office and he was one of 14 Eyes and Vietnam, who earned a battlefield commission. He was moved from speck forward a second lieutenant. He did such a fine job. Marvin and I have been friends for all of those 55 years. And so our cooperation on this new book is very special. We both know what we're talking about and how to talk to the veterans. And this book is, the full title is They Were Soldiers: The Sacrifices and Contributions of our Vietnam Veterans, and this is profiles and interviews with 48 Vietnam veterans, some very famous, some not famous at all. And what we tried to do with this is, not look so much at the war they thought, but instead focus on the lives they have lived and the good they have done for their communities and our country since that war, and I just think it's long overdue. that's a that's a generation of veterans. That's pretty much been libeled and slandered, in the movies, in the press. You know, I remember the headlines, you know, crazy Vietnam veteran shoots up post office, stuff like that. That's not who they are. That's not who I marched with in the jungles. They weren't all, or even any of them Lieutenant Calleys except Lieutenant Calley and Captain Medina (officers accused of murder in Vietnam's 1968 My Lai Massacre). They weren't baby killers. They were kids. They were 19 years old on average. And the country called them, they answered. Just like their fathers and grandfathers had before them, and they went to do the best job they could, in a very bad place, and did it to the best of their ability. 58,400 of them died in the doing that job. And they came home to no welcome, no respect, very few honors, and just got on with their lives, but always thinking, How can I help? What can I do for my community? What can I do for my fellow veterans? What can I do for this country? And, you know, they may not have been the greatest generation, but by God, they were the greatest of their generation.

Hope Hodge Seck 14:53

So there were hundreds of thousands of stories that you could have included in this book. So how did you know it down to 48?

Joe Galloway 15:02

Well, Marvin and I sat down with our Rolodexes. And we thought we knew a lot of the stories already. What are the ones that are most interesting, that tell things that the American people ought to know about Vietnam veterans? And we just picked them out. And some agreed immediately and easily, because they knew us and they knew our reputations as tellers of the truth. And when we got started interviewing, we didn't know how many we were going to come up with. We thought maybe 50, ended up with 48. And it's everybody from General Colin Powell to Fred Smith, who founded FedEx, General Barry McCaffrey, and then a lot of people that you never have heard about, but should have, and just an honor to tell their stories or let them tell their stories. I just think it's something this country needs right now.

Hope Hodge Seck 16:14

I love the the variety, seeing all these stories and and who you chose to include. You've got a conscientious objector who served in a different role in Vietnam, and a dog handler. And as you said, several general officers, and both authors take pains in the book to talk about the the generalizations that are made that are untrue, as you said, you know, calling Vietnam veterans baby killers and sort of the way that they were despised and mistreated. I did want to ask, though, do any common threads emerge as you're taking these oral histories and listening to these stories of common ways that this shared experience, I guess, made a difference?

Joe Galloway 17:00

In the continuing thread of these individual lives, if there's a common thread or there are several common threads, the first that springs to mind is their shock, anger. And for some of them, bitterness and coming home to no welcome. You know, they we all saw the film of veterans getting off the ships in New York after World War II and parading down Broadway, and there was none of that for Vietnam veterans. They came home to a country that really was ripped in half by the war that they had been sent off to fight, and nobody wanted to talk about the war they had fought. Even your mom didn't want you discussing it at the dinner table. And and that was, I think, that was searing to most Vietnam veterans. And it took them a long time. They kind of went to ground just like they did in the jungle when, when the shooting started, and it took them a lot of years to finally come out, finally start going to unit reunions and doing things they knew where in order to help fellow veterans to help other people. There was there was some bad years in there.

Hope Hodge Seck 18:38

We;re very different culture now, and I'm grateful for the fact that Americans, by and large, have a much more respect and appreciation for what American service members do. And yet there are many fewer Americans who serve and I think there's less familiarity with who service members are and what it means to be in the military. What what are your thoughts on how the nation is doing today?

Joe Galloway 19:08

I think we need to reestablish national service, not a straight draft. I would say that every American kid, male and female on reaching the age of 18, owes their country two years of service. They get paid for it. You know, they do it honorably and finish the job. They get two years free college anywhere that will have them. They want to serve in the military, it's four years, and they get four years' free ride any college in America. But I'm big on choice. Peace Corps, establish a corps for the hospitals. Kids would work there. stablish an education corps that would work in the inner city neighborhood schools to try to upgrade the education these kids are getting. Even reestablish the old Civilian Conservation Corps, which built the national parks in this country. And nobody has really repaired them since they built them back in the 30s. So send them out there to fix the parks, different things that they couldn't do, but should do. Give them ownership of a piece of America. "I did this, I served. I built that. I help these people." I think it would be really a renaissance for the young people of this country, and a renaissance for the country itself, to see young people out doing what's normal in Europe. National Service, you owe something to your country. We owe a lot to this country we live in. And you know, the problem of this is that the generals and the Pentagon, they like it just like it is right now with a volunteer army. No turnover every four years, or not much. Consequently, nobody in Congress has really looked at this thing and tried to see if they could make a go of it. And I think that's a sad thing, sad commentary. That would probably do more to build a military that's more connected to the American people. During the time of the draft, I mean, maybe 90% of the kids who got drafted absolutely hated it. They had other things in mind to do, but they didn't really have a choice, they had to go. They had to do it. They may have absolutely hated the Army, but they did the job. And they finished it and they got out and they went off actually better people for having served. I've tried to tell young journalists, you know, the closer to the base of the flagpole you get, the better the people you meet. And I think that's true.

Hope Hodge Seck 22:32

You've been writing about, consulting about, living, breathing the Vietnam War and its history for decades now. And your contribution has helped to shape what we know about the war and what we think about it. And you know, perhaps this is sort of an obtuse question, but what is the staying power of this historical event? And how did it become your life's work after your time downrange in 1965?

Joe Galloway 23:00

Well, it did become a life's work because I nearly died in Vietnam more than once, because I'm alive today because soldiers laid their lives down so that I might live to tell their story. I walked out of the Ia Drang battle with a crushing weight on my shoulders. I knew that 80 young men had died, so that I could live to tell their story. I knew that I had an obligation to tell the truth about those soldiers, and all soldiers, all our troops. At the time, it seemed like a crushing obligation. I got used to it over the years, four tours in Vietnam. I kept going back to war, not because I loved war, I hate it. It's the most foolish of all man's doings there. The only good war is when you have to literally fight them off of your front law-- they've invaded you. The rest of it, we could have done without. So I have no great love of war, but I have a great love of soldiers, those who go to fight those wars, on our behalf, under our flag. You know, often these days, the politicians don't stand up and explain to the troops, why they need to go and risk their lives in this place or that place, or any of a dozen places where their lives are at risk. They just send them, so how does the soldier deal with that? Nobody has explained to him why it's really a good thing for him to go out with the rifle and kill other young men of a different color, in a different place, who think differently. It's just orders. What I noticed, and what I find really heartening is that in those circumstances, the soldiers, the troops -- because I include the Marines very much here -- they will fight and die for the people on their, right, the people on their left, the people who are covering their rear, that's enough. They're willing to die for each other and do, and, you know, Ronald Reagan said, the Vietnam War was a noble cause. Not really. There are no noble wars, but there are noble people who fight in those wars. And those are the people I care about. And those are the people that kept me going back, not for love of the actual war, but for love those who find it. And you know, the last few times I was out, I was in my 60s, and I'm still running up and down sand dunes behind 19-year-old Marines. And somebody would say, "Wow, why are you doing this?" And it's a reasonable question. But why I was doing it is because the kids would look at me and say, you know, if that guy can live through 40 years of wars, maybe I can make it.

Hope Hodge Seck 26:51

Oh my goodness. Incredible.

Joe Galloway 26:54

Yeah.

Hope Hodge Seck 26:57

Well, I would be remiss, particularly with my audience, if I didn't give you a chance to tell a story that I'm sure you've told many times. So you received the Bronze Star in 1998, for actions in 1965, what was that experience like? Especially because it was so such a unique action for you to be given that as a civilian, how did you respond to that news, and what does that award mean to you?

Joe Galloway 27:24

I would tell you that one day I was in the Boston area and the phone rang. The fellow on the other end said, "Mr. Galloway, I'm here in the Pentagon and I have your Bronze Star with V. We would like to present it to you." And I said, "I think you've got the wrong guy. I'm a civilian. I've always been a civilian." He said, "Oh, we know that. And you know, the JAGs have been working for two years on this thing to decide that we can actually do this. So we know you're a civilian. And we want you to come to Washington and we'll have Chief of Army information, present this medal to you in his office." And I said, "I don't think so. You're not giving me the medal for being a reporter; you're giving it to me for valor in combat, the actions of a soldier. If you're going to present this, either do it in front of soldiers, or just mail the damn thing to me." And he said, "Well, you got any ideas?" And I say, well, "General (Hal) Moore and I are going to be at Fort Bragg doing a lecture to the 82nd Airborne officers and NCOs, and I can't think of a better place to do it than there." He said, "Good. That's what we'll do." And that's what they did. I don't know if you can see it, but I wear the lapel pin every day I put this coat on, because that's not for me. That's for the 70 reporters and photographers who gave up their lives in Vietnam in pursuit of the truth. That's for my buddies. And I wear it proudly. This is the only medal for valor the U.S. Army ever presented to a civilian. But the Marines did it for three of my buddies in Vietnam for the same reason: rescuing wounded American troops under enemy fire. TMarines did it as soon as the war was over and Lyndon Johnson couldn't stop them anymore. The Army waited 30 years to give me mine, at two years with the JAGs searching all the ways not to do it.

Hope Hodge Seck 29:58

And I love that you held their feet to the fire when they actually made the phone call. You said, "if you're gonna do this do, it the right way."

Joe Galloway 30:05

That's absolutely right, and it was presented by -- he was a two-star then -- Keith Kellogg and, and Hal Moore was on the stage with me. And the two of them hung the metal on me and I couldn't have been more proud.

Hope Hodge Seck 30:24

That's an amazing story. Thank you for sharing. Since you're an avid reader and writer and I know the great retired general Jim Mattis talks about the importance of reading when it comes to war fighting and understanding history and strategy -- I was wondering if you had one or more than one book recommendations for my listeners?

Joe Galloway 30:45

Oh my god, I have to tell you that my library runs to about 5 or 6,000 books and I've read them all and there are you know, it depends on what you want. You want to know about war, James Webb's books: Field of Fire. David Halberstam's books, he wrote several really super books his Korean War one-year history that I believe he called The Coldest Winter was the last book. It is an excellent, excellent read. I would recommend highly my own book with the General Hal Moore, We Were Soldiers Once and Young. You know, someone a couple of years ago did a survey of 50 or 100 military historians to pick the 10 most important war histories of all time, and we made the cut. So it's worth reading, you might learn something.

Hope Hodge Seck 31:57

Well, thank you so much. This has been an absolute pleasure of a conversation and a bucket list item for me -- I've always wanted to meet and speak with you. So thank you so much for your time and I wish you the best and stay healthy.

Joe Galloway 32:12

Thank you.

Hope Hodge Seck 32:16

Thanks for joining us again on Left of Boom. Joe Galloway's new book, co-written with Marvin J. Wolf, They Were Soldiers: The Sacrifices and Contributions of our Vietnam Veterans, went on sale in May from Nelson books. You can pick it up wherever books are sold. We'll have new episodes coming soon, so please hit subscribe and let us know what you think about the show in the feedback section. We also want to hear from you about future episodes: who do you want to hear from, and what military hot topics would you like us to tackle next? Let us know by sending us an email at podcast@military.com. And remember to stay up to date on all the news that matters to the military community every day, at Military.com.