On Easter Sunday 1945, Harry Stewart Jr. and his wingman, Walter Manning, were part of a mission to escort a B-24 Liberator bombing mission over St. Polten, Austria. They were both members of the 332nd Fighter Group, the famed Tuskegee Airmen. While the legend that they never lost a single bomber isn't true, they were particularly good at their jobs; when the bombing mission ended, seven of the 332nd's escort fighters flew on to hit targets of opportunity as the B-24s headed home.

As they flew along the Danube River, nearly a dozen fighters appeared. In the dogfight that followed, Stewart would rack up three kills, and 10 of 12 enemy ambushers went down in all. But the Tuskegee Airmen lost two of their own. Manning was one of them. When all was said and done, Stewart would receive the Distinguished Flying Cross. Manning would be captured and lynched by enemy civilians.

Those were the stakes for America's first-ever Black combat pilots. But Stewart would survive World War II as one of only four Tuskegee Airmen with three air-to-air victories in a single day, leading a storied Air Force career before leaving active duty in 1950.

Stewart died on Feb. 2, 2025, at his home in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. He was 100 years old.

Harry T. Stewart Jr. was born July 4, 1924, in Newport News, Virginia. His family moved to New York City two years later. Stewart told the National World War II Memorial he used to walk over to nearby North Beach Army Airfield (now LaGuardia Airport) as a young boy and fantasize about being the pilot of the planes taking off and landing there. That, he said, was the beginning of his fascination with flying. He would learn to fly planes before he could drive a car.

When World War II began in Europe in 1939, the United States began registering military-age men for the draft. Stewart was 16 years old, but wanted to volunteer for the U.S. Army Air Corps. He was told the Air Corps did not accept "negroes" for pilot training.

He was watching P-39 fighters take off from that same airfield when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941. He once again volunteered for service and took the exam for pilot training. By then, the Army had established an all-Black aviation training center at Tuskegee, Alabama, where segregation was the law of the land. Growing up in Queens, Stewart had no idea what segregation was until he joined the service.

"I was willing to accept that to get my wings," Stewart said in 2024. "I was willing to do anything to get my wings."

He was among the first of 1,000 Black pilots trained at Tuskegee Army Airfield in the 1940s. He graduated in June 1944, then went to South Carolina's Walterboro Field for combat training. Before the year was over, he would be in Italy, flying combat missions with the 332nd Fighter Group. He would fly 43 combat missions during World War II.

"The first couple of missions that I had, I had no idea of what was going on except that I was keeping close to my leader at the time there," Stewart told Northeast Public Radio in 2020. "I got to really enjoy the idea of the panorama of the scene I would see before me, with the hundreds of bombers and the hundreds of fighter planes up there and all of them pulling the condensation trails, and it was just the ballet in the sky and a feeling of belonging to something that was really big. I must say that even though it was war time, I found it exciting and enjoyable."

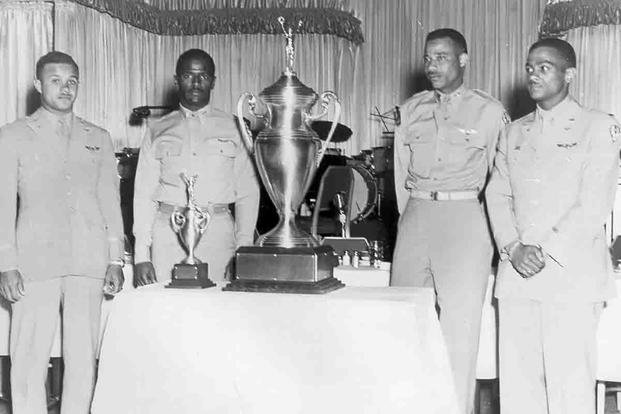

Stewart stayed in the Army Air Forces after the war, and he remained after it became the U.S. Air Force in 1947. In 1949, he was part of the four-man team that represented the 332nd to compete in the USAF's first aerial gunnery competition, the first-ever "Top Gun"-style wargame. His team, which included James Harvey, Alva Temple, Halbert Alexander and Buford A. Johnson won the "Top Gun' prize despite flying obsolete aircraft. It was a win the Air Force essentially hid until 1995.

Read Next: The Tuskegee Airmen Won the First Air Force 'Top Gun' Aerial Gunnery Competition

Stewart left the Air Force in 1950 as part of the U.S. military's postwar force reductions, but remained in the Air Force Reserve, later retiring as a lieutenant colonel. He tried to get a job flying commercial airliners in his postmilitary life, but the still-segregated airline industry wasn't accepting Black pilots. Instead, he attended New York University to learn engineering and went to work at ANR Pipeline Company in Detroit, where he would retire as vice president in 1976.

After retiring, he took to the skies once more, flying local children to inspire them to become aviators well into his 80s.

"[I was] hoping that maybe someday, one or two of them might decide that they would take in piloting as a vocation, which they did," he said in 2020. "And there are a couple of kids that I had flown during that time now who are currently flying with the airlines."

Harry Stewart Jr. recounted his life and career in his 2019 memoir, "Soaring to Glory: A Tuskegee Airman's Firsthand Account of World War II."

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.